Disaster Fiction

Just as people recall the circumstances under which they first heard the news of the attack on Pearl Harbor, so they will remember how the atomic bomb first burst upon their consciousness.

—Scientific Monthly, September 1945

The Republic did not survive the use of atomic weapons. The bomb tore a hole in our reality. Ever since, normalcy and sanity have become lost technologies. The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, engaging in cargo cult ritual, are, in the dimmest haze, aware what they do is shamanism yet, against the tide of unreality raining down from the hole in the sky, they are defenseless.

The atomic bomb’s clandestine development during World War II through the Manhattan Project, veiled in secrecy from even high-ranking officials, forged the template for a nuclear security framework that would forever reshape American governance.

The war had already militarized the sciences, but the bomb’s deployment in August 1945—effectively on par with conventional carpet bombing, but a truly devastating psychological weapon, a weapon against all mind—ended the war and thrust the nation into post-apocalyptic paranoia. The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 would establish the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) with sweeping powers to classify and control the nuclear Prometheus. Much of science became a secret art, and secrecy became the artful science.

It is as though the Bomb has become one of those categories of Being, like Space and Time, that…are built into the very structure of Our minds, giving shape and meaning to all our perceptions…Would not a history of “nuclear” thought and culture become indistinguishable from a history of all contemporary thought and culture?

—by the Bomb's Early Light, Paul Boyer

Time's first postwar issue declared that the bomb had “split open the universe” and “created a bottomless wound in the living conscience of the race.” Since that moment, all things even notionally adjacent to the Manhattan Project were slated for weird, extramundane destinies. As example, the number of scientists and personnel from the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) and the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) who were all fated for ARTICHOKE or UFO-related research projects by 1950.

In the 1950s, a wave of UFO sightings around nuclear test and storage sites manifested; Manhattan scientists became Doomsday sages quoting the Bhagavad Gita on television; Roswell, part of the Manhattan Project and home to the 509th—the unit that dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki—became a central mythologem of 20th century folklore. The Manhattan alumni formed a secret nation bound in universal madness. Every “norm” presupposes a normal situation, and no norm can be valid in a perpetually abnormal situation. How does one govern the new irradiated tellurium without making a god of Secrecy?

Sovereign is he who decides the exception.

—Carl Schmitt

The bomb became the vehicle for introducing unprecedented levels of secrecy and paranoia into the public and private mind. In fact, it was the portal through which a new kind of uranium-enriched “super-paranoia” spread into the world. As the Cold War dawned, this escalating delirium propelled the passage of the National Security Act of 1947, giving birth to the CIA for covert intelligence and the National Security Council for vizier-like advising—both formed to counter the threat of simian Soviet eyes on Anglo-American designs. Then, the Soviet Union’s nuclear test on August 29, 1949, which shattered America’s atomic monopoly, ratcheted these covert mechanisms, leveraging justification from a new tellurium founded on an ever-shifting labyrinth of secrecy and criminal sovereignty.

The entire apparatus of nuclear security has escaped democratic political control in that the technology involved so radically telescopes the time involved in operational decision-making and so restricts it to a small circle of persons that it does become a simple matter of the "morally exacting" decision. In that sense we do have a very dear "sovereign" and a perpetual prospect of the state of exception.… [t]he effect of this condition on the rest of the polity is considerable. The nudear-security apparatus reserves to itself considerable powers of control over economic resources, special police measures, etc., and has a capacity for secret policy-making whose limits are difficult to determine. If we take Schmitt's claim that "sovereign is he who decides on the exception" seriously, then most of our formal constitutional doctrines are junk.

—Hirst, P. 1987. Carl Schmitt’s Decisionism. Telos

The bomb, and all that followed from it, split the US into a schizophrenic “dual state,” ratcheting the national security complex into a leviathan-sized shadow government. Following Schmittian onto-politics, we find a number of “exceptions” appearing around the nuclear-security apparatus. So many, in fact, that we must identify the nuclear-security complex as the primal “sovereign.”

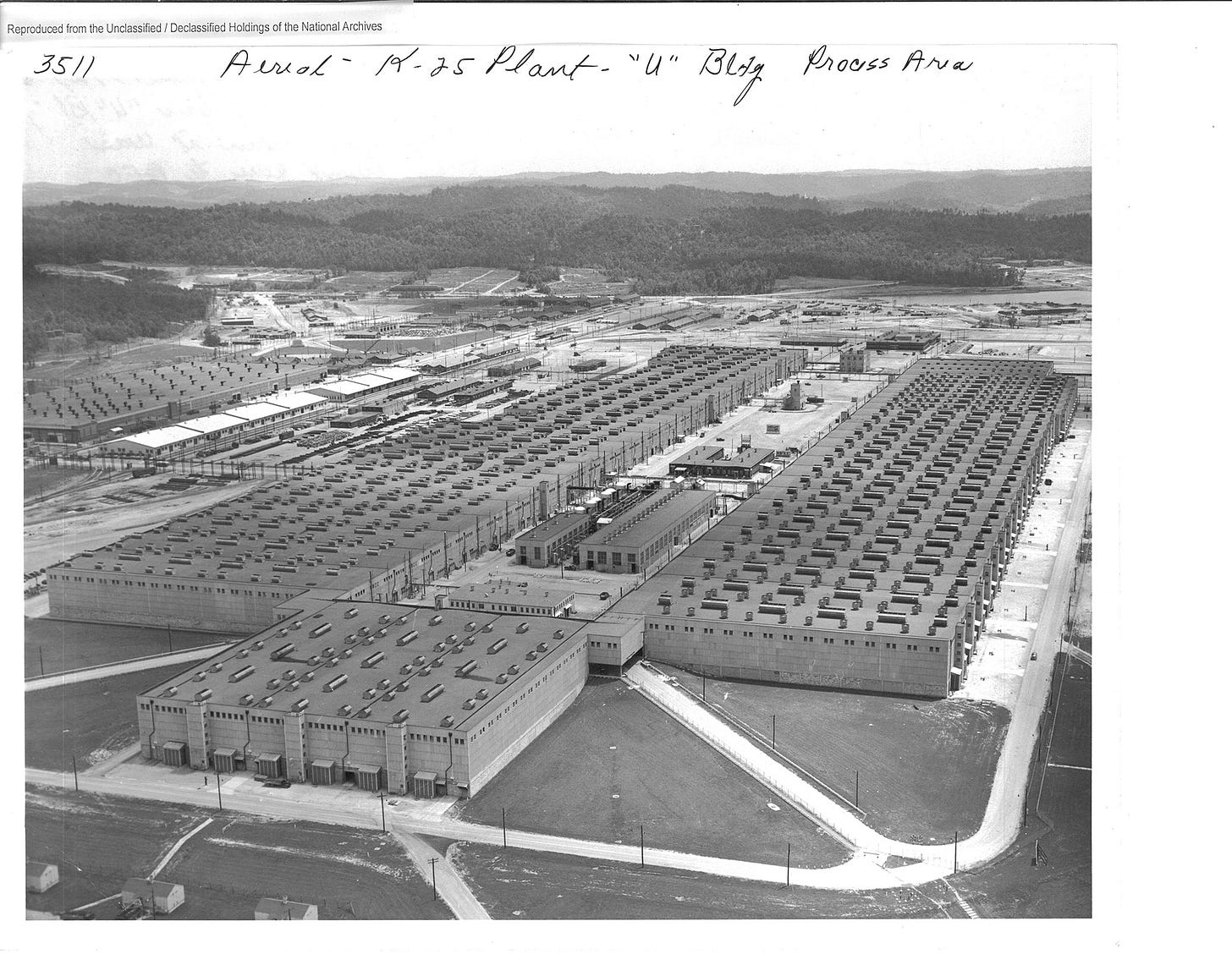

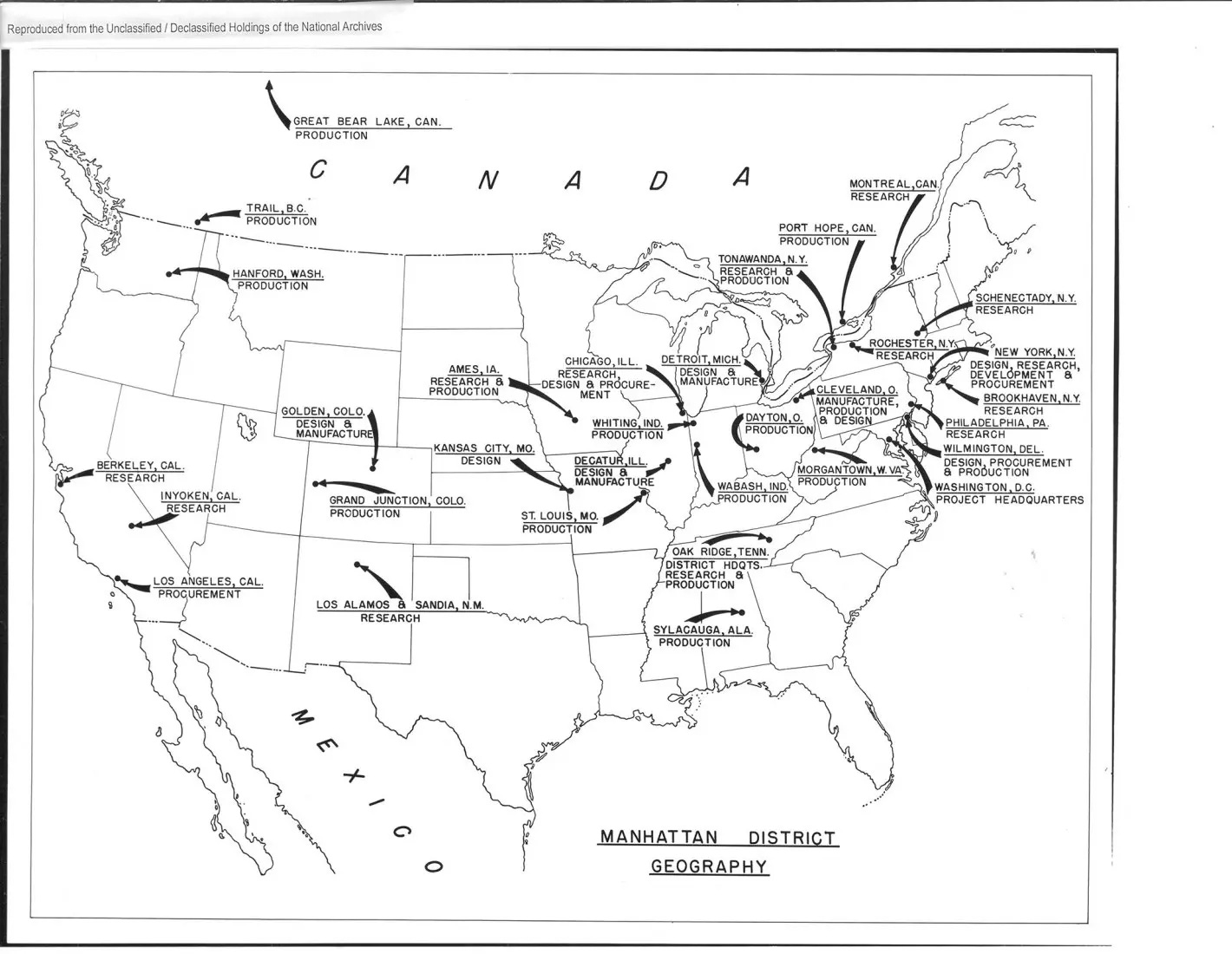

The nuclear ratchet effect, building on Higgs’ (1987) framework in Crisis and Leviathan, posits that “existential threats”—initiated by the discovery of nuclear fission and exacerbated by Hitler’s warning: “Make no mistake…The moment could come very suddenly in which we could use a weapon with which we cannot be attacked.” (Hitler 1939)—compelled the U.S. government to launch irreversible expansions like the Manhattan Project (the largest research project in the history of mankind, constituting a quasi-state with its own energy plants and intelligence organization), which cost $2.2 billion and employed 130,000 workers, thereby permanently increasing the scale and scope of nuclear weapons policy.

This primary crisis-induced expansion was further accelerated by a secondary calamity, the USSR’s first nuclear detonation in 1949, which initiated exponential increases in U.S. nuclear warhead inventories—from 170 in 1949 to over 31,200 by 1967—and catalyzed the establishment of new agencies and intelligence operations, such as the ALSOS mission and Project Paperclip.

The nuclear bomb is a weapon of exception. Its birth required the building of secret citadels—Oak Ridge, Hanford/Richland, and Los Alamos—and was itself born in crypsis as invincible liminality, guardian of the threshold between peace and apocalypse, the decision point between alternate timelines, a conqueror of martial realities and the social imagination. Then, in the 1950s, the atomic beast was wet-nursed to intercontinental size by extrajudicially acquired genius, initiating a chain reaction of grim comedies that continue to warp social, political and medical realities to this day.