Human experimentation is the cutting edge of human sacrifice, and the propitiated deity is not always Science. There is a chimerical trail of gore that leads from the sacrificial altar to the alchemist, to the laboratory. Throughout history, whether it was the dignity of the dead, orphan children, the mentally ill, or unaccompanied women, the skinsuited thing we call ‘doctor’ has always been ready to sacrifice the vulnerable. In 2020, when it became feasible to experiment on the global middle class, a white-cloaked leech brood was suddenly assembled, producing unproven elixirs from thin air.

One might wonder, if tomorrow the human bioflow became “disordered” once more, if, by chance, some circumstance made it permissible for our medico-bureaucratic cult to conduct “necessary and life-saving” head trauma research on the world, would that shoggoth surge forth again, clutching a hammer in every tentacle? Would it writhe in the ecstasies of media-anointed authority as it initiated a new class of martyrs into its mysteries? And how many glorious thanatonautes would go willingly?

”According to the social control hypothesis, human sacrifice legitimizes class-based power distinctions by combining displays of ultimate authority—the taking of a life—with supernatural justifications that sanctify authority as divinely ordained.”

—Watts et al (2016). Ritual human sacrifice promoted and sustained the evolution of stratified societies.

The practice of human sacrifice—the ritualized killing of an individual to gain favor with supernatural beings—is found throughout the archaeological record of prehistoric civilizations, the traditions of indigenous cultures, and the holy texts of contemporary religions. It functions as a means to maintain social stratification and has been used as a technique to “punish taboo violations, demoralize underclasses, mark class boundaries, and instill fear of social elites“(Watts et al, 2016) Sacrificial victims tend to be from the lower strata: prisoners, orphans, prostitutes, people with disabilities, the mentally ill, hospital patients, slaves, and the conquered (Chamayou 2008). On the surface, it appears that egalitarian, “free” societies like ours tend not to have much in the way of ritual murder. However, in the Western world, there is but a simulation of egalitarianism that serves only to equalize mass man to the level of a lab rat and encrypt the rituals of human sacrifice.

In 1952, MacFarlane Burnet, the Nobel prize-winning virologist, stated that medical research had separated from human needs. (Burnet, Macf. Lancet 1953 pp.103-8) There is a kind of ‘breakaway medical civilization’ that operates in parallel to ours. Like Bacon’s scientocratic island, its inhabitants stay sequestered but regularly send out ships to raid the unsuspecting nations for objects of fascination. “We have consultations, which of the inventions and experiences which we have discovered shall be published, and which not; and take all an oath of secrecy for the concealing of those which we think fit to keep secret; though some of those we do reveal sometime to the State, and some not.” (Bacon 1635)

This hidden regime seeks to make the whole world their subjects. Throughout history, there has been a periodic raiding of fresh bodies, a feeding frenzy of the medical shoggoth. One such took place in the Ptolemaic era in Egypt, where a small group of elite Greeks ruled over the population. This is where“Herophilus and Erasistratus… laid open men whilst alive – criminals received out of prison from the kings – and while these were still breathing, observed parts which beforehand nature had concealed” (Celsus: De Medicina).

Herophilus is regarded as the first person known to engage in the systematic dissection of the human body. It was there, in the Ptolemaic convergence of cultures and occultures, the ‘frontier environment’ of Alexandria, where the hallowed altar for those first medical sacrifices was concretized. Such an atmosphere was required for these rituals because “[r]espect for the dead would have prevented this under the Egyptian pharaohs and also in Greece itself” (Nunn, 1996). Herophilus transgressed upon the Egyptian dead and even sacrificed the living to his curiosity, in the breaching of spiritual and religious boundaries he invoked a great malediction. A mummy curse that slumbered for an eon, and then awoke in the form of Egyptianism—

”There is ... their hatred of even the idea of becoming, their Egyptianism. They

think they are doing a thing honour when they dehistoricise it, sub specie aeterni—when they make a mummy of it. All that philosophers have handled for millennia has been conceptual mummies; nothing actual has escaped their hands alive. They kill, they stuff, when they worship, these conceptual idolaters—they become a mortal danger to everything when they worship. Death, change, age, as well as procreation and growth, are for them objections—refutations even. What is, does not become; what becomes is not … Now they all believe, even to the point of despair, in that which is.”

—Friedrich Nietzche, Twilight of the Idols

Such Egyptianism is based on a desire for a 'reduction to the pristine state', for an end to the living process. As Herman Weyl asserts, “[t]he objective world simply is, it does not happen.” This mummified corpse of reality has been smuggled through the centuries until it emerged encased in the sarcophagus of Cartesian metaphysics. Lo, the hidden project of the idolatrous mechanists— a system of interlocking cartouches that would facilitate control over Nature and humans; in other words, the primordial vivisectionists introduced a social necromancy where individuals were to be reduced into quantifiable units and bureaucratically organized. An undead and alien assumption of knowledge. This paradigm seeks to isolate the object from its field, disintegrate holistic entities and complex organizations into base elements, and embalm phenomena in the “residue of a metaphor”. This total annihilation of creative evolution leaves no room for the richness and royalty of life, it leaves us, as Nietzsche reminds us, with “illusions which we have forgotten are illusions; they are metaphors that have become worn out and have been drained of sensuous force, coins which have lost their embossing and are now considered as metal and no longer as coins.”

As societies stratify the rate of human sacrifice increases. As stratification evolves so too do the forms and reasons for sacrifice. China, for example, has the longest history of human sacrifice in the world, lasting from Neolithic times down to the twentieth century. The reasons and occasions for human sacrifice in that country have been innumerable, with ritual performances ranging from baroque refinement to avant-garde ‘struggle sessions’. Another awe-inspiring example is the sophistication of the Aztec mass sacrifice cult that was broadly popular among the population, considered an honor, a glorious end, and a great source of social capital:

Sacrifice, as the 'main act' of huge feasts and festivals, was indeed hailed as a 'great deed'. Victims usually died 'center-stage' amidst the full splendor of dancing troupes, orchestras, elaborate costumes and decorations, carpets of flowers, crowds of thousands, and all the assembled elite.

The glorified victim was the Aztec equivalent of a celebrity or rock star; they were 'sighed for' and 'longed for' by the audience. Their deaths merited a public announcement and their names were immortalized in the local 'roll of honor'. Commemorated in songs, poems, and epics, the deceased was further honored by the euillotl (human effigies) their relatives had constructed from pine log torches and decorated with paper wings and jackets. These effigies were burnt in memory of the victim for two days, and they took pride of place in the heart of town. Indeed, sacrifices were made to a euillotl, as though to a god.”

—Dark Religion? Aztec Perspectives on Human Sacrifice, Ray Kerkhove

Most ethnographies ignore the testimony of actual Aztecs. Theories focusing on a lack of protein and cannibalism have been disproven, many researchers who examine the statements and conditions of the Aztecs have discarded such models, “finding little evidence of Mesoamerican kingdoms being unusually totalitarian, and that 'mere oppression' could not explain ‘how the trick worked’. Finally, it now seems Mesoamericans despised and tightly controlled the use of narcotics and inflicted far harsher punishments than the modem West.” (Kerkhove, 2008)

This demonstrates that it is perfectly possible, even without television or the internet, to have a population adore their own mass sacrifice. To not even consider it as death, but a new life. Unfortunately, the Aztecs did not have the mass communication systems available today. We can only imagine electrified Aztecs with a robust mediasphere. Sadly, we’ll never know if they could achieve parity with us and convince the greater part of their population to sacrifice mind, body, and spirit for mere virtual applause.

The grim specter Jack Kevorkian, otherwise known as “Dr. Death”, in his article A brief history of experimentation on condemned and executed humans, published in the Journal of the National Medical Association in 1985, argues that “all condemned persons should be allowed to choose to submit to experimentation”. In justifying this proposal he draws parallels to the practice of human sacrifice in Homeric Greece and the Mayan Yucatan—

”No definite records have survived to verify direct evidence of experiments on the condemned in Homeric Greece. Those who find such experimentations plausible point to the quality of medical knowledge attributed to physicians in Homer's works. This suggests to them that its only possible basis was the

direct observation afforded by dissection of the human body. Some of the latter might have been alive and selected to serve as "food" for the gods in ritual human sacrifices, a common practice during that period.”

”In the Religion of Modern Medicine, the rite of vivisection is central. The medical student acolyte, early in his preclinical years in the seminary called medical school, learns live animal dissection in physiology and pharmacology classes. The religious significance of this practice is implanted deeply into his unconscious by his teachers, who train him, at the end of each experiment, not to kill the animal, nor to dispose of it, but to ‘sacrifice’ it.”

—Foreward to Slaughter of the Innocent by Hans Reusch, Robert S. Mendelsohn, M.D (1983)

The term “sacrifice” comes from the Latin sacer facere, which means “to make holy” (Bell, 1997; Hubert and Mauss, 1964). This word is commonly used by scientists to describe methods for killing laboratory animals. According to Durkheim, the word "sacrifice" signifies a process of making something sacred and transmitting it between profane and sacred realms. The violence done to the animal victim and its body during this process is part of a systematic consecration, transforming it into a pure abstraction, translating it into the supernal realms of information, subtle bodies of pure data.

Scientists don't think of their practices as rituals endowed with religious significance but laboratory "sacrifices" are just one step in the transformation into a transcendental object that has special meaning for members of the medico-bureaucratic cult. Instead of generating mana or divine succor, this generates the arcane substance called data, arguably an abstraction of less real-world utility in most cases. The scientists are reducing the whole, vital animal to an “analytic object”, consisting of interlocking mechanisms. Of course, as we have intuited by now, Reductionism is a system of cosmic nihilism that masquerades behind a so-called scientific method—

“Physical atomism is more than logical analysis. It is the assumption that there is a quantitative limit to division, and that small ultimate units exist.... Atomism has rightly been described as a policy for research... But atomism is not merely a policy or a method that has proven brilliantly effective at certain levels of material analysis; it is also a positive assumption regarding ultimate structure. This assumption has a powerful psychological appeal, for it suggests a limited task with high rewards. If there exist ultimate units, we have only to discover their laws and all their possible combinations, and we shall be all-knowing and all-powerful, like gods.”

—Lancelot L. Whyte, Essay on Atomism: From Democritus to 1960 (1961)

As you may already know, today’s ‘institutional reductionism’ has many of its roots in alchemy and other strains of esoteric transhumanism. Materialistic monism is the mutated inversion of John Dee’s hieroglyphic monad, a universal kryptogon for locking away the process of becoming. Ironically, it is born from the same desire to master reality, achieve immortality, and attain godhood. The first chemist Robert Boyle was an aspirant to such chymical arcana as the philosophers’ stone, alkahest, chrysopoeia and was interested in the “nature, communities, laws, Politicks and government of spirits”.

Regarding the Philosophers’ Stone’s effects, Boyle believed, “there may be congruities or magnetism capable of inviting [spirits] which we know nothing of,” and “such persons as the Adepti may well be supposd to be under a peculiar conduct and to have particular privileges” concerning spirit contact and communication." (Chalmers, 1993). With a probability approaching absolute certainty, Boyle was channeling some of his ideas from “angelic” entities. However, today he is simply remembered as the father of modern chemistry and one of the first to apply the metaphysical philosophies of reductionism and mechanism—

“Boyle’s mechanical or corpuscular hypothesis is spelled out in most detail in ‘The Origin of Forms and Qualities According to the Corpuscular Philosophy’ although the general features of it are described by Boyle in many of his works. A key feature of it is its reductionist character. All the phenomena of the material world are to be reduced to the action of matter and motion . . . In the following, I use the term ‘corpuscle’ to refer to minima [i.e., Boyle’s prima naturalia] only. Each corpuscle possesses a determinate shape, size, and degree of motion or rest… For Boyle the secondary qualities are to be reduced to, that is, explained in terms of, the primary ones. More specifically, all the phenomena of the material world are to be explained in terms of the shapes, sizes, and motions of corpuscles together with the spatial arrangements of those corpuscles amongst themselves.”

—.Alan Chalmers, “The Lack of Excellence of Boyle’sMechanical Philosophy,” Studies in history and Philosophy of Science 24 (1993)

In 1565, Ambroise Paré, the so-called “father of surgery” recounted an experiment to test the properties of the Bezoars Stone. At the time, the Bezoar stone was believed to be able to cure the effects of all poisons, but Paré theorized this was impossible. It occurred that a cook at Paré’s court was caught stealing fine silver cutlery. The cook was sentenced to be hanged but Paré had other uses for his flesh— if he agreed to be poisoned he would receive a pardon. The barber-surgeon then used the Bezoars stone to no great effect as the cook died in agony days later.

The mad scientist Paré has been credited as the respectable “father of surgery” with many innovations accredited to him as an attempt to camouflage and conceal the magical roots of medical science and divert attention away from characters like Leonardo Fioravanti—

”The ancient idea of the magical wound-healing balm—tied to the conviction that wounds caused by a new kind of weaponry required a new kind of balm—gave rise to an alchemical quest that Fioravanti eagerly joined. Leonardo did, after all, have a new way of healing wounds. It was composed of four ingredients: a medieval surgical procedure, the science of alchemy, the folklore of wound-healing balms, and skills learned in the heat of battle. And it was little different from the method that academically trained Paré claimed to have invented. Yet Leonardo Fioravanti, unlike Ambroise Paré, went down in the history of modern medicine as an arch-charlatan, not a hero.

So why does the legend of Ambroise Paré persist in the history of medicine? Why do we seem to need the style of history that elevates heroes such as Paré? Perhaps it is because the medical profession has a driving need to confirm that, despite the uncertainty surrounding its everyday practice, modern medicine is, after all, a rational, scientific, and progressive discipline. During the 19th century, and for much of the 20th as well, the history of medicine—written mainly by physicians—was deployed as an instrument in the ongoing professionalization of the field. The elaborately constructed “war against charlatanism” was an integral part of the medical profession’s strategy to preserve the domain of medicine for specialists.”

—The Professor of Secrets: Mystery, Medicine and Alchemy in Renaissance Italy (National Geographic Books, 2010)

Though they have successfully distanced themselves from their reputation as charlatans, traveling hacks bilking the peasantry, most scientific work today is still self-promotional or proselytic. It is the mass production of novel, fashionable theories that sell. The entire direction and philosophy of medical research have been distorted by funding from the state or other powerful actors for decades:

”In the case of the medical literature, it is now fairly well known in academic medicine that pharmaceutical companies launder their promotional efforts through medical communication companies that ghostwrite articles and then pay ‘key opinion leaders,’ chosen for their influence on prescribing physicians, to affix their signatures to the fraudulent articles.”

—McHenry L. (2008). Biomedical research and corporate interests: a question of academic freedom.

Popper (1959) observes, “In so far as a scientific statement speaks about reality, it must be falsifiable: and in so far as it is not falsifiable, it does not speak about reality.” However, there is little interest in falsification because reality is, to a disturbing degree, not a scientific concern. Scientists are often too busy researching the ecosystem of grant money being disseminated through a great mycelial network of NGOs by pharmaceutical giants. The fact that modern science has a very tenuous connection to reality has been more or less proven by the ongoing “replication crisis”:

”The inability for researchers to reproduce many of the findings of past studies is causing particular concern in several disciplines, including psychology and the medical sciences. Indeed, one recent study suggests that “irreproducible preclinical research exceeds 50%” of all studies.3 The poor reproducibility of experimental findings in any discipline can be due to problems with experimental design, statistical errors, small sample sizes, outcome switching,4 selective reporting of significant results (p-hacking),5 failure to report negative results,6 or journal publication biases which favor positive over negative results and “newsworthy” over confirmatory research.7,8”

—Coiera, Enrico et al. “Does health informatics have a replication crisis?.” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association

If most researchers are not “sacrificing” their victims for the sake of discovery, then unto what exactly are they propitiating? The philosopher Hans Jonas has suggested that human experimentation is a "solemn execution of a supreme, sacral necessity"; "something sacrificial [in their] abrogation of personal inviolability and the ritualized exposure to gratuitous risk of health and life, justified by a presumed greater, social good." In a scientific paper that has apparently been scrubbed from the internet we hear "[Conducting] controlled studies may well sacrifice a generation of women but scientifically [they] have merit."(G. Robbins, The Case for Radical Surgery, 1977)

”The term, 'sacrifice' is a naturally occurring metaphor, used by laboratory scientists as a name for methods of killing an animal so as to transform it into data. The term resonates with traditional religious significance, and scientists are not oblivious to these significances. Beyond the obvious use of the term to justify the destruction of animals for the 'higher' causes of scientific knowledge and medical progress, are several more detailed analogies between the transformation of the 'naturalistic' to the 'analytic' animal, and that of the 'profane' to the 'sacred' object in religious ritual…

Sacrifice can also be something of a 'rite of passage' for participants in the laboratory's research since it is among the first tasks assigned to new members. Successfully performing lesion and sacrifice operations on a cohort of rats enables the novice to acquire 'material' for his or her own experiments. At the same time, the practices constitute a threshold for the novice to get his or her 'hands dirty', personally, in a direct, participatory, transformation of self and animal.”

—Sacrifice and the Transformation of the Animal Body into a Scientific Object: Laboratory Culture and Ritual Practice in the Neurosciences, Michael E. Lynch

After Herophilus there seems to be a great gulf before the next experiments begin, some say this is due to Galen of Pergamon. Bernard Knight, M.D., in his book, Discovering The Human Body, discusses the legacy of the prolific anatomist: “Galen’s grip on the minds of learned men was so complete that it was considered heresy to dispute his conclusions,” Knight said. “ After his death, in about A.D. 201, men stopped doing medical research for more than 1,000 years, since it was believed that Galen had discovered all there was to know, and further work was therefore futile.”

However, this isn’t entirely accurate. The Byzantine historian Theophanes (752–818) records how “an apostate from the Christian faith and leader of the Scamari, was captured. They cut off his hands and feet on the Mole of St Thomas, brought in physicians, and dissected him from his pubic region to his chest while he was alive. This they did with a view to understanding the structure of man. In this condition, they gave him over to the flames.”

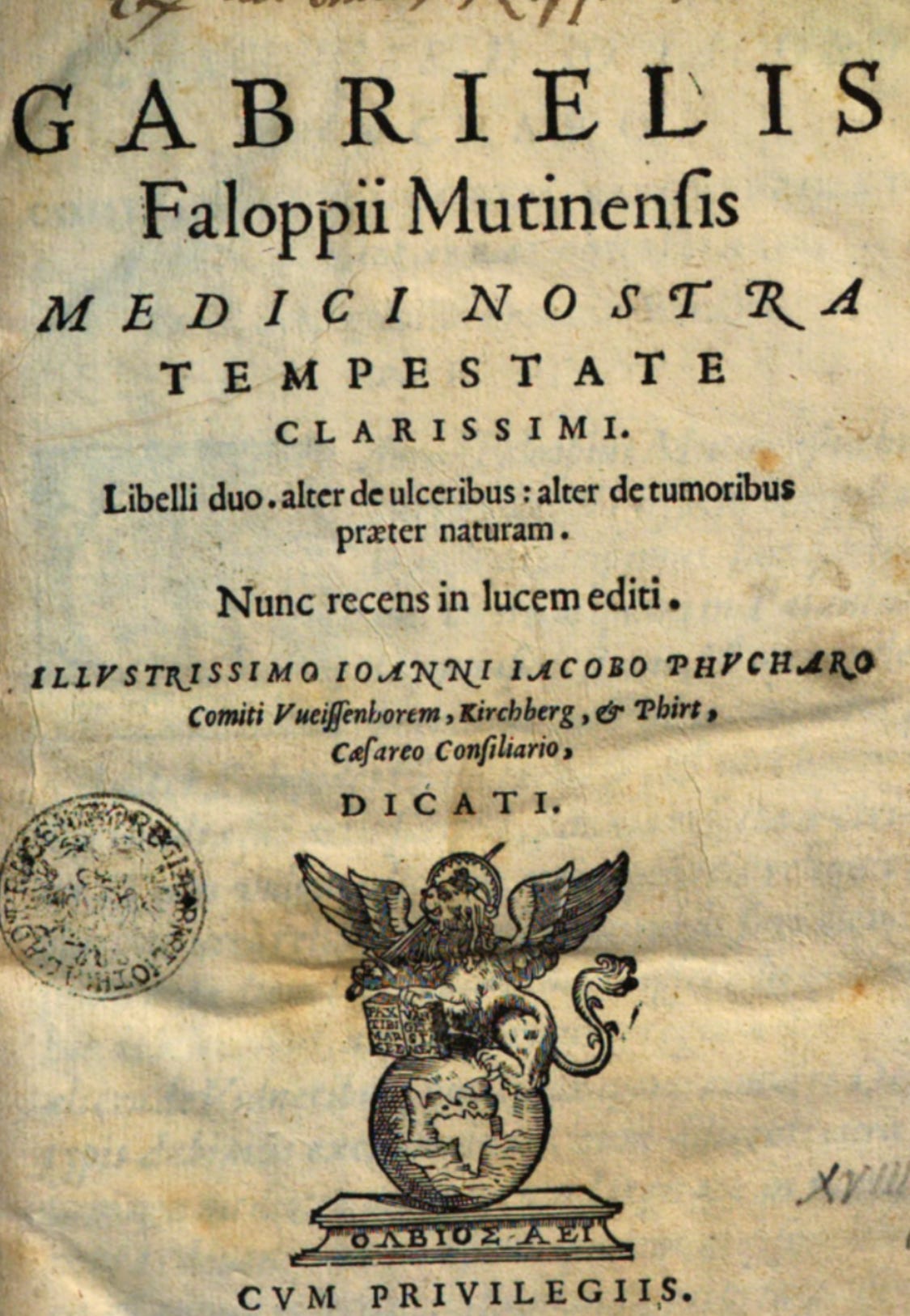

There are doubtless many more experiments that have been lost to the abyss of time. Unless we have primary sources, such precious revelations can always fall prey to ‘the forgetting animal’. To illustrate, in 1563, the Grand Duke of Tuscany gave Vesalius' pupil, Gabriele Fallopius custody of a condemned criminal to conduct atrocious experiments. The condemned was suffering from quartan fever and Fallopius wished to test the therapeutic efficacy of opium, but an initial dose of three drams during a paroxysm had no effect. So the second dose of three drams was given; this time the result was death. Though the historicity of this gruesome tale is vehemently contested by medical propagandists, the professor's words in his book prove otherwise.

The medical cult protects its own. Indeed, the objectivity of scientists and doctors is itself a cult object, a fetishistic mask that the doctor dons, allowing him to evoke a distance between himself and the subject. But even when the mask drops and the diabolical conspiracies of doctors are discovered they’re often completely suppressed, surgically excised from the historical record. For instance, one such case occurred in a hospital in Geneva, 1545—

”that all those who would be brought to Hospital, instead of cure them, if they did not die [quickly], they would kill them, by poison or otherwise. After they were dead, they drew the plague of the carbuncle that they had on their bodies… then put it into powder, mixed with other drugs, from which they gave drink to the plague-stricken, pretending that it was a healing drink. Not content with that, after Caddo had served his term at Hospital, they powdered beautiful handkerchiefs with this poison, well-crafted, beautiful garters and the like, then they went through the city at night, leaving them to fall here and there, mainly in front of the houses”

—Chroniques de Genève, Book 2, 559

The first modern, publicized use of human experimentation came in the context of smallpox variolation in London in the early 1720s. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu experimented on her own children, including her three-year-old daughter, which then inspired royal physician Hans Sloane to arrange for an experimental trial. Six prisoners from London’s Newgate prison, three men and three women condemned to be hung were offered a pardon in exchange for their souls. Upon the seeming success of this initial trial, the human guinea pig experiments were immediately extended, on the orders of the Princess of Wales— this time to children. In March 1822, it was officially reported that five orphans from St James’ Parish, Westminster, had successfully undergone the operation.

Absolute evidence of human experimentation will always be scarce, it is rarely reported on and even contemporary incidents are unknown by the public. A successful experiment is welcomed by historians and the media as a miracle of science, but a failed experiment is essentially murder. We can assume that many orphans were subjected to the injection of infected “swine matter” and subsequently vanished. From the evidence we do have, it is possible to demonstrate the bizarre attitudes and entitlement of physicians when they sought credit for their “successful” experiments and published their deeds. From the details of the strange relationships that physicians develop with their experimental subjects, we can infer that many unsuccessful experiments likely have occurred in subterranean darkness.

To give us perspective on this, we have the series of articles in the Lancet written by William Wallace of Dublin in 1836 where he precisely detailed how he had succeeded in inducing classic syphilis by inoculation of material from secondary lesions of the disease.

He goes into gory detail, describing the application of diseased animal matter and the various symptoms that arise. However, the exact number of research subjects needed for these trials is not disclosed in The Lancet, but we can assume they were numerous. Wallace does however provide some details, revealing that he experimented on several children including three boys between the ages of 10 and 14. Because these boys were foundlings and blind, they were considered by Wallace to be “especially suited for the experiment, as they will spend the entire life in a shelter for the ailing and will always remain under medical observation.”

The question of consent is seldom raised, the phrase “informed consent” wouldn’t be discovered by physicians for another century. In May 1796, the famous vaccine pioneer Edward Jenner “selected” James Phipps, an eight-year-old local boy, for an experiment (Jenner, 1798). In the literature, the ambiguity of the relationship is never noted. How was this child selected, how was consent procured, and why did Jenner later buy him a house with a rose garden? Was that part of the deal, did Jenner approach an 8-year-old boy and offer him a house if he would only submit to an injection of his diseased animal matter?

Although countless unethical experiments on the poor and orphans were described in medical journals and at scientific meetings of the nineteenth century, they aroused zero protests from physician colleagues of the investigators. (Meyers 2003) This strange culture of doctors, viewing any unprotected human as a potential specimen, continues throughout the 20th century and up until this day.

Much of the documentation on human experimentation can be extremely hard to uncover. First, because historians of medical science are often doctors themselves, and secondly because of the jargon which was consciously designed to “professionalize” the medical industry and to obscure its activities. One such magic word is “xenotransplantation”.

Serge Abrahamovitch Voronoff was a French surgeon “of Russian extraction” who became well known in his time for grafting the tissue of monkey testicles onto the testicles of men. Voronoff also attempted to transplant monkey ovaries into women and then reversed the experiment, transplanting a human ovary into a female monkey. Of course, overcome with scientific passion, he also attempted to inseminate the monkey. These experiments earned him the nickname "monkey gland man" and various parodies and plays were scripted at his expense. Though eventually denigrated by the medical community, Voronoff became very rich from transplanting ape tissues to about 2000 human patients throughout his career.

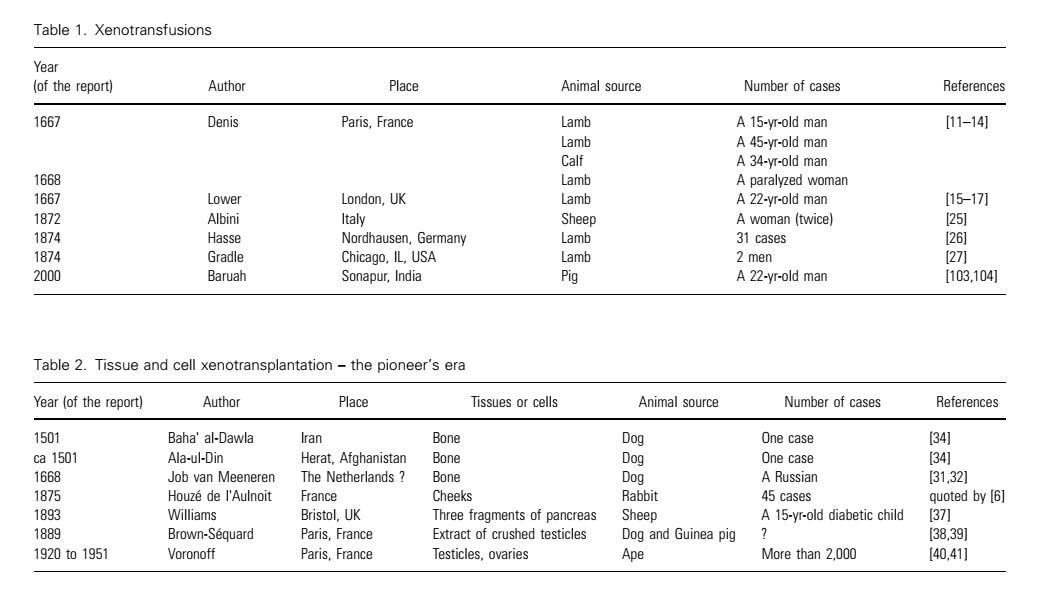

Reading about Voronoff and his peculiarities, one would assume he was an anomaly (as such is the intention). However, Voronoff simply represents a rare extrusion into the public mind of a long, dark history. The very first documented description of a transfusion to man is “a xenotransfusion realized on June 15, 1667 by Jean-Baptiste Denis, a French physician, doctor of King Louis XIV, and Paul Emmerez, surgeon, transfused the blood of a lamb to a 15-yr-old young man. The man, with a severe fever, was cured. Denis and Emmerez thus proved ‘‘the effects that the mixture of different types of blood could produce’’. Supported by this ‘‘success’’, Denis realized other xenotransfusions. One was a xenotransfusion of calf blood to a 34-year-old mentally ill man named Antoine Mauroy, in the hope that this would cure his madness. In December 1667, after a first success, the signs of madness reappeared and two other transfusions were made. After the last one, on Monday, December 19, 1667, the patient died the following night” (Deschamps 2005)

Cont.—

We come to recent history with Albert Moll and his Medical Ethics (1902). Moll summarized around 600 research papers that explicitly or implicitly reported non-therapeutic experimental interventions on human subjects. These were collected from the international literature, throughout the 19th century human experimentation was commonplace in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, France, Italy, England, Russia, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Romania, the United States, Chile, and Egypt.

”I have observed with increasing surprise that many medics, obsessed by a kind of research mania, have ignored the areas of law and morality in a most problematic manner. For them, the freedom of research goes so far that it destroys any consideration for others. The borderline between human beings and animals is blurred for them. The unfortunate sick person who has entrusted herself to their treatment is shamefully betrayed by them, her trust is betrayed, and the human being is degraded to a guinea pig. Some of these cases have occurred in clinics whose directors cannot talk enough about ‘humanitarianism’, so that they may almost be regarded as specialists in humanitarianism. There seem to be no national or political borders for this aberration.”

—Ärztliche Ethik : die Pflichten des Arztes in allen Beziehungen seiner Thätigkeit, Albert Moll (1902)

Around the same time, The American Humane Society published a pamphlet titled, Human Vivisection: A Statement and an Inquiry. In this document, they reported on the widespread human experimentation on the mentally ill, women, and orphans. There exists only the briefest reporting on this document in a few academic papers so I will examine it in some detail here.

The pamphlet cited the above from “a paper recording some experiments on infants to determine whether lumbar puncture of the subarachnoid space is dangerous.” The physician justified himself by saying “The diagnostic value of puncture of the subarachnoid space is so evident that I considered myself justified in incurring some risk to settle the question of its danger.” Science demanded that he puncture the spines of babies. The document notes that he did not obtain permission and there was no therapeutic value, these actions were purely experimental.

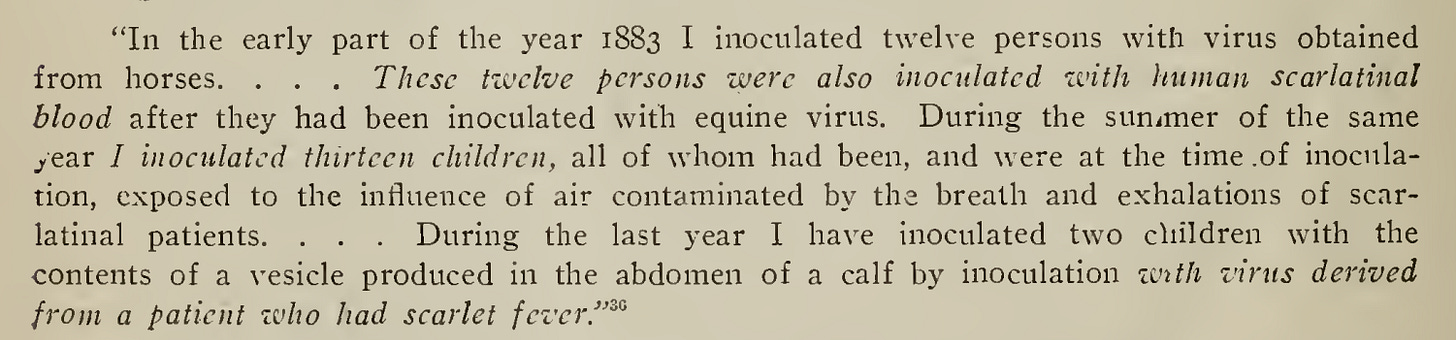

Another physician in Honolulu decided to sate his curiosity with an experiment on children with leprosy, he wanted to inflict them with syphilis to see if it had any effect. In his words "On Nov. 14, 1883, I inoculated with the virus of syphilis, . . . six leper girls under twelve years of age. December 14th, following, I repeated the experiment; this last time, I used fourteen points and inoculated fourteen lepers therefrom, but no result followed in any of the twenty experiments. For the suggestion of this experiment, I am indebted to my friend, Dr. E. Pontoppiddan of Copenhagen, Denmark. I am not aware that anyone else has ever attempted to inoculate a leper with a syphilis virus. Since coming to San Fransisco, I have tried on several occasions to get the opportunity, but so far without success. . . . While the twenty cases in which I inoculated syphilis on lepers are not absolutely conclusive, still it is a point worth considering. It is to be hoped that this experiment should be tried by competent observers under more favorable circumstances.”

It is to be noted that this statement was not obtained under confession, this creature published these words in a medical journal, as did all of the 600 papers compiled by Albert Moll and other dissenters. As the pamphlet decries, not a single medical journal protested against his experiments on little girls. Just this incident alone demonstrates that the medical field itself is structurally complicit.

This document is extraordinary in that it was written before the last century of paradigm shifts, resets, and accompanying re-edits of the encyclopedias. Casually referencing the Encyclopedia Britannica they reveal—

“But that eminent American physiologist, Dr. John W. Draper, ascribes the zeal of one of these princes to less creditable motives. Ptolemy Philadelphus, he tells us, toward the close of his life was haunted by an intolerable fear of death, and devoted much time to the discovery of an elixir; for this purpose, there was a laboratory; and ‘in spite of the prejudices of the age, there was, in connection with the Medical Department, an anatomical room for the dissection,-not only of the dead but actually of the living, who for crimes had been condemned.’ Dr. Payne, in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, speaking of the dissections of Herophilus, asserts that ‘there is no doubt that the organs were also examined by opening the bodies of living persons.’”

The record continues, detailing what was found in the Criminal Archives of Florence, by a certain Prof. Andreozzi: during the reign of Cosimo de Medici, condemned criminals were from time to time sent to the scientists of Pisa, there to be "anatomized." Even though these were criminals, the knowledge that they were dissected while still alive in a medical theater rightfully inspires horror.

Indeed, it is a grand tradition that undergirds a more enlightened doctor when he inoculates a patient with cancer cells, depositing cancer particles in healthy parts of their bodies, and producing fresh cancer growths. Another injects 40 newborn babies with tuberculin at fifty times the maximum dose. Another published that he poisoned 10 children with Salicine, after which he went on to poison whoever came into his presence with an assortment of substances, all of his mad hijinks were submitted for peer review.

The section titles continue “Inoculation of Children with Syphilis”, “Inoculation of Mothers with the Vilest of Diseases”, “Experiments on Pauper Women and New-born Babies”, “Inoculation with Tuberculin and Germs of Consumption”(also on new-born babies), and this one that I find the most illustrative— “Children Cheaper than Calves for Vivisection”.

The doctor explains, "When I began my experiments with smallpox pus, I should, perhaps; have chosen animals for the purpose. But the fittest subjects, calves, were obtainable only at considerable cost. There was, besides, the cost of their keep, so I concluded to make my experiments upon the children of the Foundlings' Home.”

The pamphlet concludes with outraged questions, “Why has no word been uttered by them against scientific murder? Has it indeed become ‘a pardonable crime’? What is your opinion regarding the experiments here reported? Do you approve of child sacrifice, if only it is done in the ‘interests of Science?’”

In the next four decades of the 20th century, the antivivisectionist movement that published this document would protest the use of orphans in the trials of new vaccines and diagnostic tests for syphilis, tuberculosis, diphtheria, and other infectious diseases. Unfortunately, to little avail— 20 years later in 1921, Konrad Bercovici, a social worker, and novelist published an article in the Nation where he criticized the use of “orphans as guinea pigs”:

“No devotion to science, no thought of the greater good to the greater number, can for an instant justify the experimenting on helpless infants, children pathetically abandoned by fate and entrusted to the community for their safeguarding. Voluntary consent by adults should of course be the sine qua non of scientific experimentation” (Bercovici, 1921)

Ten years later, 76 children died from the administration of B.C.G. vaccine contaminated with virulent tuberculosis cultures in Lübeck, Germany. The sheer number of victims was too much to ignore, the public was appalled and new restrictions were put in place. In another 15 years, after the Second World War, 23 Nazi medical defendants were put on trial for atrocities, including medical research. Had the Weimar Republic of 1931 been defeated, would the murderers of those 76 children also be charged for war crimes?

The point is that Nazi doctors were working in the context of a medical culture that accepted and valued non-therapeutic human experimentation. Unless the number of dead was excessive, no physician or researcher raised an eyebrow at the human carnage produced by medical experimentation. Those who want to deny such brutal experimentation took place in any country that participated in WW2 are arguing from ahistorical exceptionalism. Prisoners or vulnerable populations have always been selected for martyrdom by the priesthood of the medical cult.

We can only imagine what arcane research, beyond the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and MKUltra, which the Allied powers and their more favored clients might be condemned for in the alternate timeline where the US was defeated in the last century. Many have heard about the famous “twins studies” of Josef Mengele, but, for some reason, few are aware that equally appalling incidents were occurring in Japan. Between 1931 and 1945, Japanese army doctor Shiro Ishii conducted experiments on prisoners in Unit 731, short for Manshu Detachment 731 in the puppet state of Manchukou—

”These [experiments] included tying armored individuals to stakes and dropping anthrax bombs in the nearby vicinity to observe the impact and timeframe of biological killing; spreading plague bacilli experiments including hypothermia experiments similar to those conducted in the Allies, in particular, the US, could not have been more different. In a deliberate and systematic cover-up, the US State-War-Navy Coordinating Subcommittee (SWNCC) granted total immunity to Ishii and his colleagues in return for the acquisition of all available data collated from the experiments. This position was extraordinary given its contemporaneity with the Nuremberg trials. So too was the rationale for granting immunity – in the interests of national security – astonishing defense of their crimes. A telegram from Washington to the SWNCC read: “since any war crimes trial would completely reveal such data to all nations, it is felt that such publicity must be avoided in the interests of defense and security in the US. It is also believed that ‘war crimes’ prosecution of Ishii and his associates would serve to stop the flow of much additional information of a technical and scientific nature”

—Of Mice and Men: Violence and Human Experimentation, Rawlinson (2013)

The data must flow. Many sympathize with researchers and their desire to push forward the boundaries of science. This is why there is often very little criticism heard against the use of prison populations for human experimentation. I show examples of prison experiments not to elicit sympathy, but to demonstrate how doctors operate when they have access to captive populations, whether they are restrained by bars or “mandates”. Coercion is not always clearly defined, there may be unarticulated penalties, the withdrawal of “privileges”, or psychological manipulation which renders the population vulnerable to exploitation and nullifies the mirage of consent (Schuklenk 2000)—

”Between 1915 and the early 1970s, many experiments were conducted on American prison populations, ranging from testicular implants to research on tuberculosis, cancer, and malaria. The peak of prison experimenting occurred between 1951 and 1974 at Holmesburg Prison in Philadelphia, which journalist Allen Hornblum described in his book Acres of Skin (1999). Directing these experiments was dermatologist Albert Kligman… inmates tested consumer products such as detergents and hair dyes as well as radioactive, hallucinogenic, infectious, and toxic materials for pharmaceutical companies and government agencies.”

—The Human Experimental Subject: Lightman/Companion (2016)

Institutional coercion also played a part in the deliberate infection of mentally ill children at Willowbrook State School in New York. Consent from parents was sought however, letters were sent by those conducting trials to minimize and obfuscate any risks involved with the trial:

Almost every phrase in the particular letter encourages parents to commit their children to the unit. The team is “studying” hepatitis, not doing human experimentation. The virus “is introduced” in the passive voice, rather than the team’s being said to feed the child a live virus… a claim of “no attack” [of the disease] was false… Finally, the letter twice described introducing the live virus as “a new form of prevention” but feeding a child hepatitis hardly amounted to prevention. In truth, the goal of the experiment was to create, not deliver, a new form of protection. (Rothman and Rothman 1984: 266)

From the early 20th century up until 1999, Australian orphanages provided the human material for a litany of obscene human experiments. These illicit trials include the testing of vaccines for diphtheria, whooping cough, herpes, measles, polio, and human pituitary hormones. “Eighty-three babies aged six to eight months old [who] had been infected with the disease when the experimental agent was found to be worthless.” (Murray 2007). Aboriginal children were injected with serums designed for the treatment of leprosy. One of the physicians involved, Dr. Norman Wethenhall, excused his nightmarish crimes by saying “it was not a mistake at the time but only a mistake by today’s standards”.

In the 1940s, one of the physicians who participated in the infamous Tuskegee experiments, Dr. John Charles Cutler, went to Guatemala to do medical experiments. He was funded by the venerable U.S. National Institutes of Health to expose 1,300 people to sexually transmitted diseases deliberately. First with prostitutes and later by hand with his wife taking photographs. Researchers often focus on the obscene details of the experiment, rather than focus on the fact that he was fully sanctioned to do these experiments—

”Cutler dutifully reported all this “progress” to his superiors in Washington, who were quite impressed. One wrote to him that “your show [!] is already attracting rather wide and favorable attention up here.” Another relayed a conversation he’d had with the U.S. surgeon general: “A merry twinkle came into his eye when he said, ‘You know, we couldn’t do such an experiment in this country.’”

—The Icepick Surgeon, Sam Kean

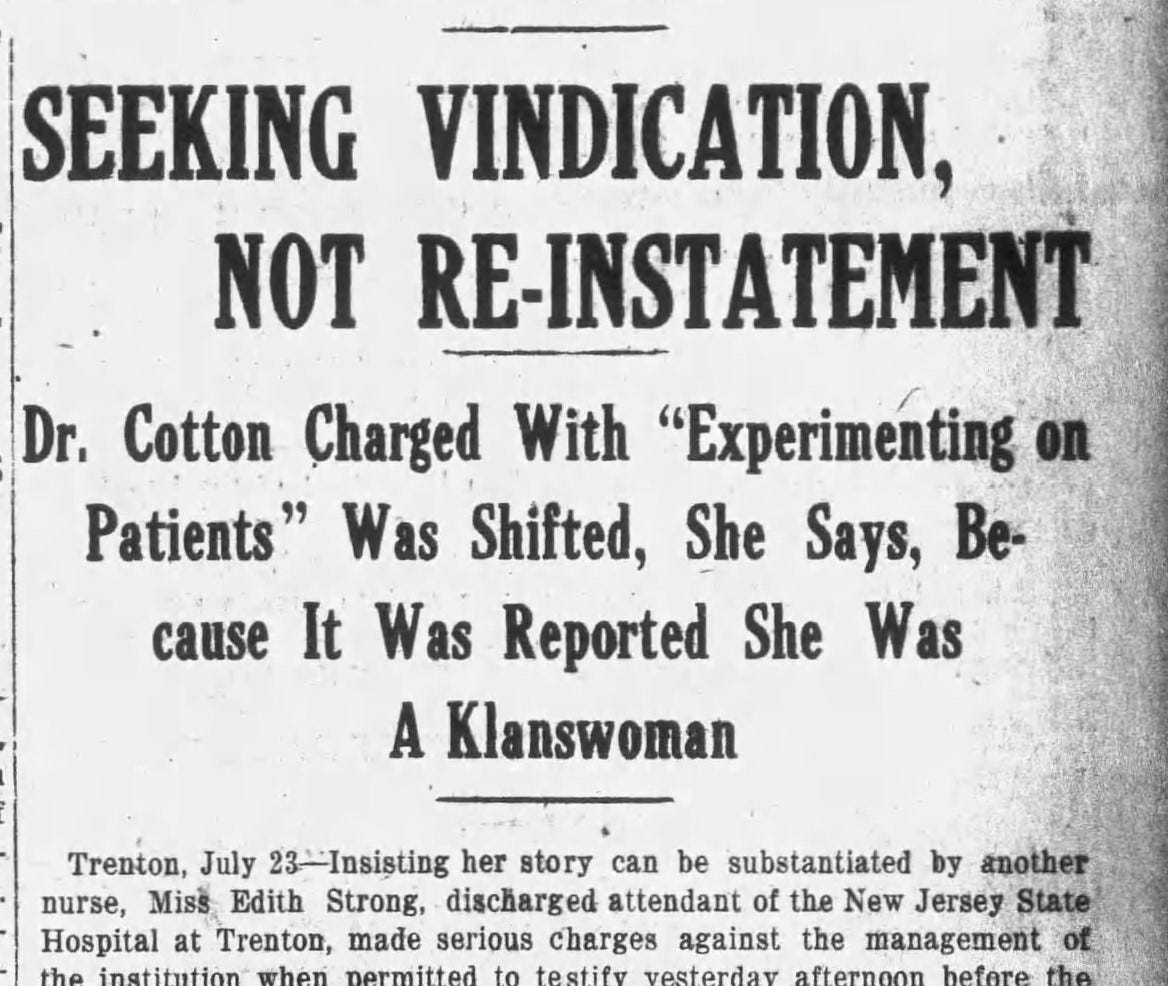

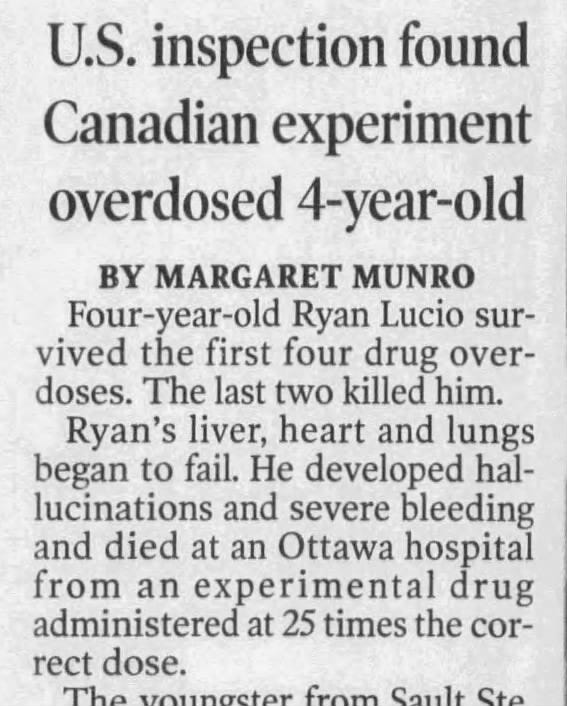

One of the great gifts of the information age has been the mass archiving of newspapers. When one reads an article here or there about some medical scandal, it appears that illicit medical experimentation is the result of one or two sketchy physicians. This conclusion is often encouraged by the media as they tend to focus on the doctor’s idiosyncrasies, that he was “unauthorized” and not the institutional context. When one looks at the vast number of abuse over the last century it becomes clear: stepping foot into a hospital transforms the human into an experimental subject.

Beginning around the mid-1960s there seems to be an explosion of reports. As we know, this was the era of widespread social and psychological experiments being conducted by states, foundations, and NGOs on national populations and cultures. It was in this climate that doctors seemed to have taken free reign with their patients, or perhaps it was such incidents became so numerous reports were impossible to suppress.

I could fill this article with clippings (I have so far about 200 of these), but the image becomes clear very quickly. Despite claims of “tabloid” or “sensational” journalism, in reality, there is a well-known historical reluctance on the part of the media to report on institutional medical malfeasance. The overriding journo instinct is to glorify human experimentation. For example, in sanctifying the sacrifices of “soldiers of research” the New York Times informed readers in 1958 that “... among these men and women you will find those who will take shots of the new vaccines, who will swallow radioactive drugs, who will fly higher than anyone else, who will watch malaria-infected mosquitos feed on their bare arms.” Regardless, due to their sheer regularity, many cases still manage to find their way onto the back pages.

Another whistleblower who revealed human experimentation as a conventional activity was Henry Knowles Beecher. In 1966 he published an article on unethical medical experimentation in the New England Journal of Medicine — "Ethics and Clinical Research". In his detailed history of human experimentation, The Abuse of Man, Wolgang Weyers M.D. informs us—

”Beecher’s article provided brief summaries of 22 experiments on humans that were objectionable ethically, including four conducted at Harvard Medical School and its affiliated hospitals and three at the Clinical Center of the NIH. In almost all 22 studies, the test subjects were institutionalized or were in other situations that compromised their ability to give free con¬ sent, such as being newborns, very elderly, terminally ill, mentally disabled children, soldiers, or charity patients in a hospital. Because Beecher wanted to avoid a “condemnation of individuals,” he gave neither names nor provided references, but the examples he published were recognizable easily to many readers. Among them were the experimental injection of cancer cells by Chester Southam, the artificial induction of hepatitis in inmates of Willowbrook State School by Saul Krugman, and the study of the effects of thymectomy on the survival of skin homografts by Robert Milton Zollinger and colleagues at Harvard.17 Perhaps the most bizarre experiment related by Beecher was the transplantation by coworkers at Northwestern University Medical School in 1961 of a cutaneous malignant melanoma from a daughter to her mother. The experiment was conducted “in the hope of gaining a little better understanding of cancer immunity and in the hope that the production of tumor antibodies might be helpful in the treatment of the cancer patient.”

In Human Guinea Pigs (1969) M.H. Pappworth revealed hundreds of human experimentation cases involving thousands of patients, which he discovered simply by perusing British and American medical journals. He demonstrated that such experimentation was a normal function of the medical industry. At the time the public was shocked and several other expositions of medical monstrosity were published, some of which I have referenced here. Despite the creation of advisory boards and other dubious safeguards, illicit, unethical, and unconscionable scientific research continues to this day.

In this new era, doctors and pharmaceutical companies have revolutionized their approach and begun to openly experiment on the global population, seeking to enforce participation in their mad transhumanist experiments through health policy and menticide campaigns. When the callous character and systemic corruption of the international medical industry are taken into account, the concept of a global medical hoax emerges out of the dark territory of conspiracy. The pressing of human bodies into the service of science, on an industrial scale, not only becomes possible, it becomes inevitable. Under the thin white coat of 20th-century ‘professionalization’ campaigns, such is the obscene anatomy of the medical shoggoth.

Excellent, thank you!