Psychotronic television acts as a cipher, an enigma ensconced in light and shadow, broadcasted across the ether of human cognition. It is a play of moving images, a parade of sign and symbol, of dialogues and metalogues, all converging in the psyche of the viewer. Yet, its existence spans far beyond the flickering screen, extending into the realm of ideas, of cultural significance, and egregoric perception. Its physical manifestation is but a fraction of its total being; a larger, grander existence unfurls in the realm of consciousness, in the symbolic and the subliminal, in the perceived and the unperceived.

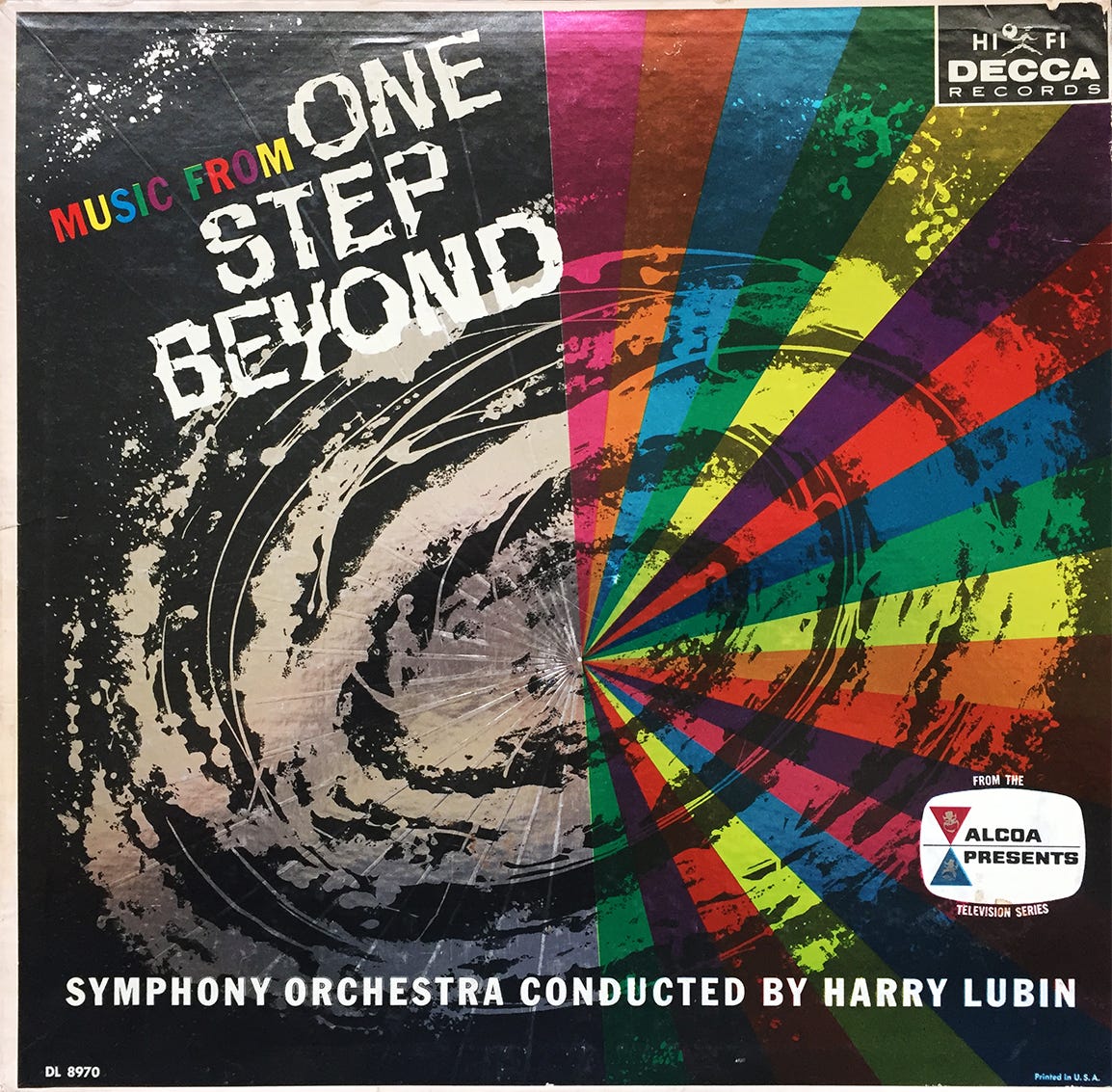

In the late 1950s, a show emerged as a conduit, a portal into the twilight zone of the human mind, existing between fact and parafiction, a televisual tunnel into the dreamland beneath Lab Madness.

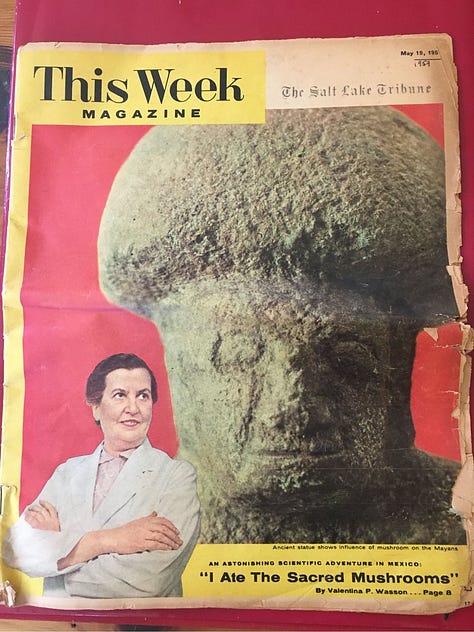

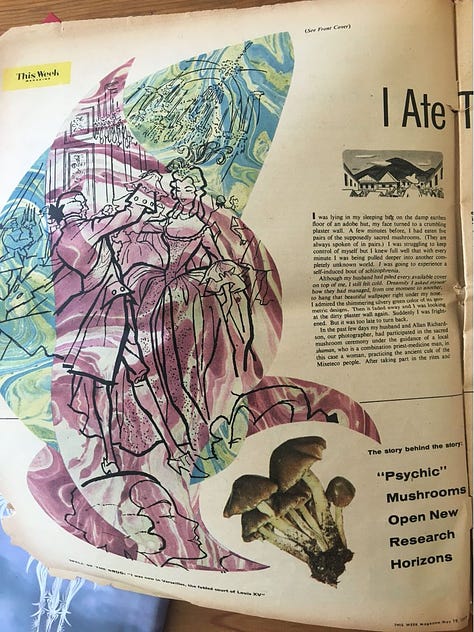

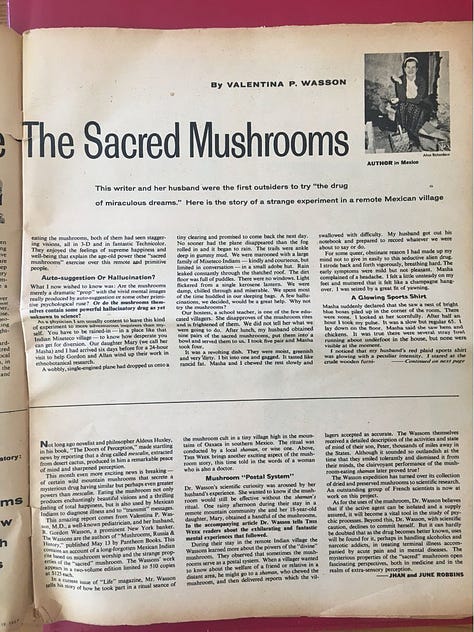

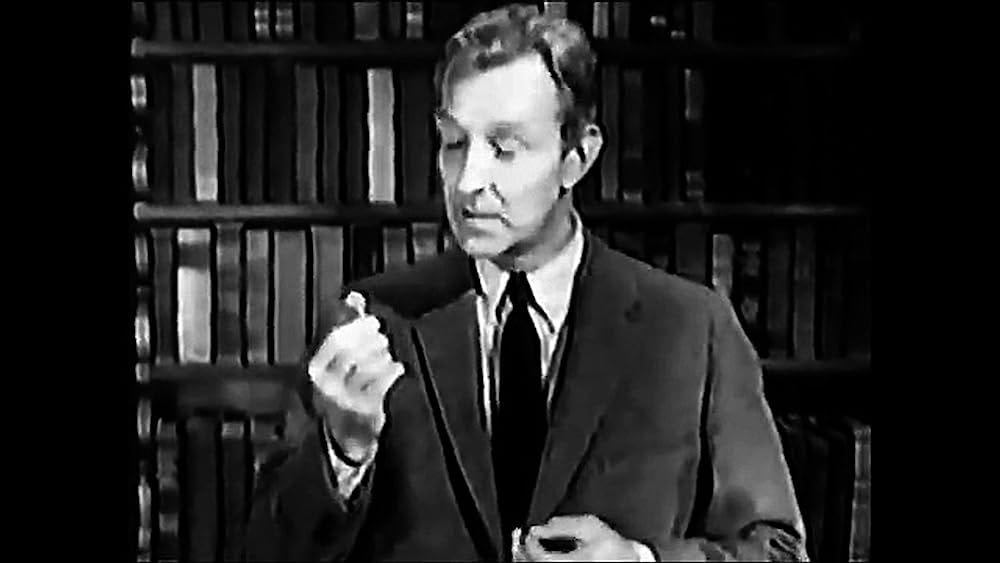

In an episode of One Step Beyond aired on January 4th, 1961, John Newland, the show's director and host, under laboratory conditions, consumed psilocybin - a substance derived from specific types of mushrooms, known for its hallucinogenic effects.

This televised human experiment was seemingly influenced by The Sacred Mushroom, a book published in 1959 by parapsychologist Andrija Puharich. Puharich is notable for bringing the controversial figure Uri Geller, a man claiming to possess psychic powers including spoon bending, to the United States for examination.

During the first segment of the episode, viewers follow Newland, Puharich, and their team as they journey to Mexico to gather mushroom samples. Afterward, they return to Puharich's laboratory in Palo Alto, California. Here, Newland's ESP abilities are assessed before and after he ingests several stems of the hallucinogenic mushrooms.

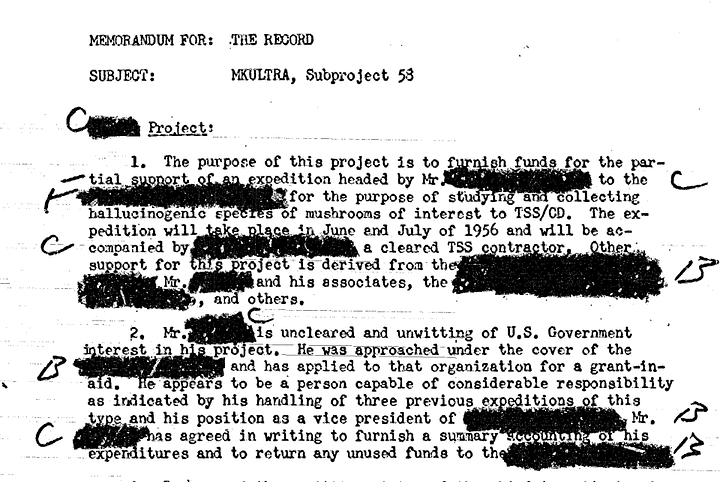

During the height of MKULTRA, Dr. Puharich was employed at the Army Chemical Center in Edgewood, Maryland, where he would remain for two years. He was tasked with overseeing soldiers' general health and working on a research project to enhance ESP using drugs. According to HP Albarelli in 'A Terrible Mistake', Puharich was involved extensively in human experiments at a number of prisons and at the Spring Grove Mental Hospital. While at Edgewood, Puharich was challenged “to find [a] drug that could bring out this [ESP] ability, to allow normal people to turn it on and off at will.”

The strange, Hitchcockian "One Step Beyond" was an anthology television series, which debuted in 1959, taking viewers on journeys into the "world of the unknown". The series, hosted by John Newland, focused on supposedly factual, supernatural phenomena, with Newland citing “the human record.”

Each episode of the show ran for 30 minutes, presented in a docu-drama format. The storylines were often drawn from urban legends and explored themes such as hauntings, premonitions, astral projections, and particularly, extrasensory perception (ESP). The series premiered before the more famous "The Twilight Zone" and was endorsed by the latter's creator, Rod Serling.

Despite criticism and allegations of being the "Antichrist" for presenting stories based on real-life tragedies and for its bizarre, paranormal content, Newland persisted. The show's production quality was extremely high, hence it needing a sponsor: the sinister Alcoa Corporation.1 The popular narrative of 1950s television being dominated by "patriarchal" themes is contradicted by the very existence of this show. But, in its third season, the whiplash the audience must have experienced as the show, for one episode, transformed into a documentary featuring a military-sponsored parapsychologist is nearly too overwhelming to contemplate.

We can only speculate on the true extent of the public backlash to the program, but One Step Beyond merely marks the midpoint in a decade-long journey characterized by psychological warfare, conducted by mainstream media endorsing the use of psychotomimetic2 substances. Indeed, there is more than enough evidence to prove that the 60s “psychedelic counterculture” was an elite operation.

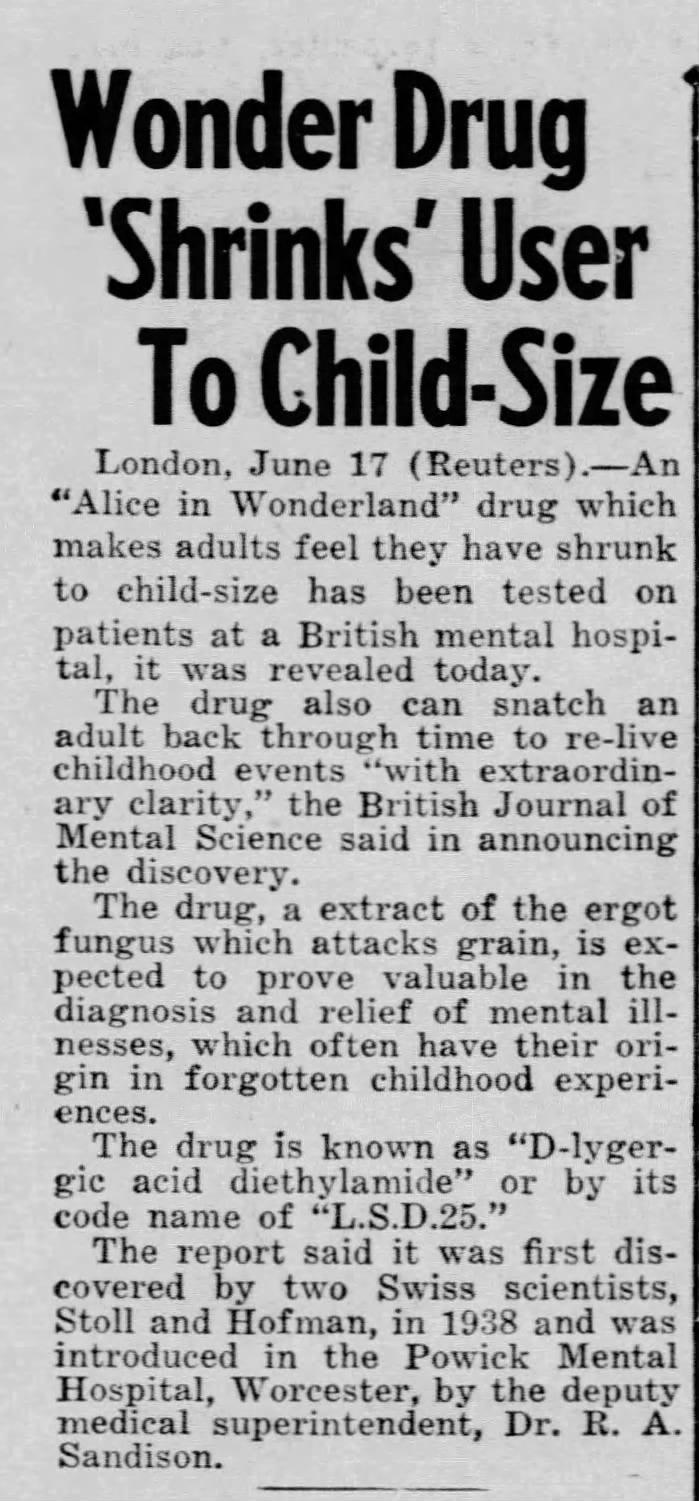

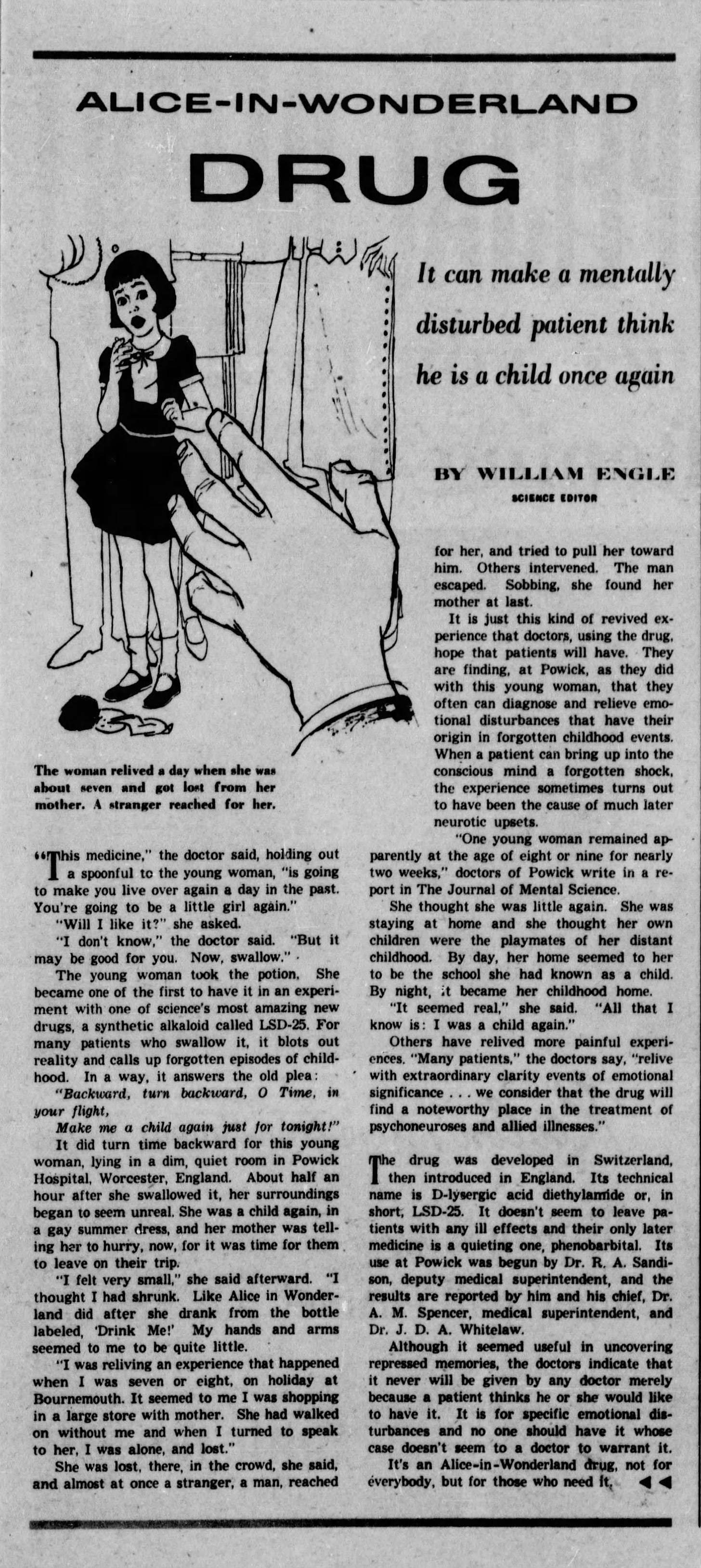

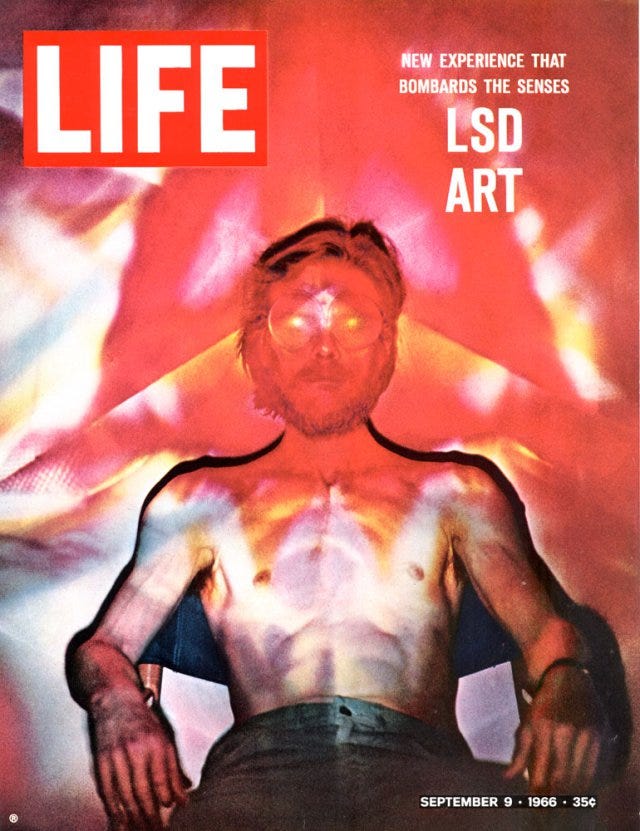

From inception to completion, “acid hype” was a top down culture war campaign achieved through mainstream print and television media. Between the mid-1950s to early 1960s, most Americans who had neither personal experience with the still-obscure experimental drug LSD, nor an inherent drive to learn about it, were nonetheless inundated by mass media coverage. This exposure came in the form of an endless slew of magazine and newspaper articles, television documentaries, and radio programs. In his book, Acid Hype, Stephen Siff concludes:

The magazines ushered in not only a new use of drugs but also a new use of media. Coverage of LSD and other hallucinogenic drugs during the 1950s and 1960s shows how media was used to achieve a previously unrecognized set of gratifications, including sensations of mystical insight and phantasmagoric escape. Over the years, mainstream audiences became accustomed to accessing these sensations first through magazines, then music and moving pictures, until ultimately psychedelic experience was associated as much with its expression through media as the drugged state that had been its inspiration. Through intensive hype of LSD and psychedelic phenomena, the news media demonstrated the transporting, mind-expanding power not only of drugs, but also of journalism.

Incredibly, written in 2015, Acid Hype takes for granted the nature of 1950s-60s “journalism” and presents it as something organic, almost completely without context.

Lo, straight is the gate and narrow is the way which leads to Hollow World. The media's role in mainstreaming schizogenic substances is already acknowledged. Now, we go one step beyond.

American Trip

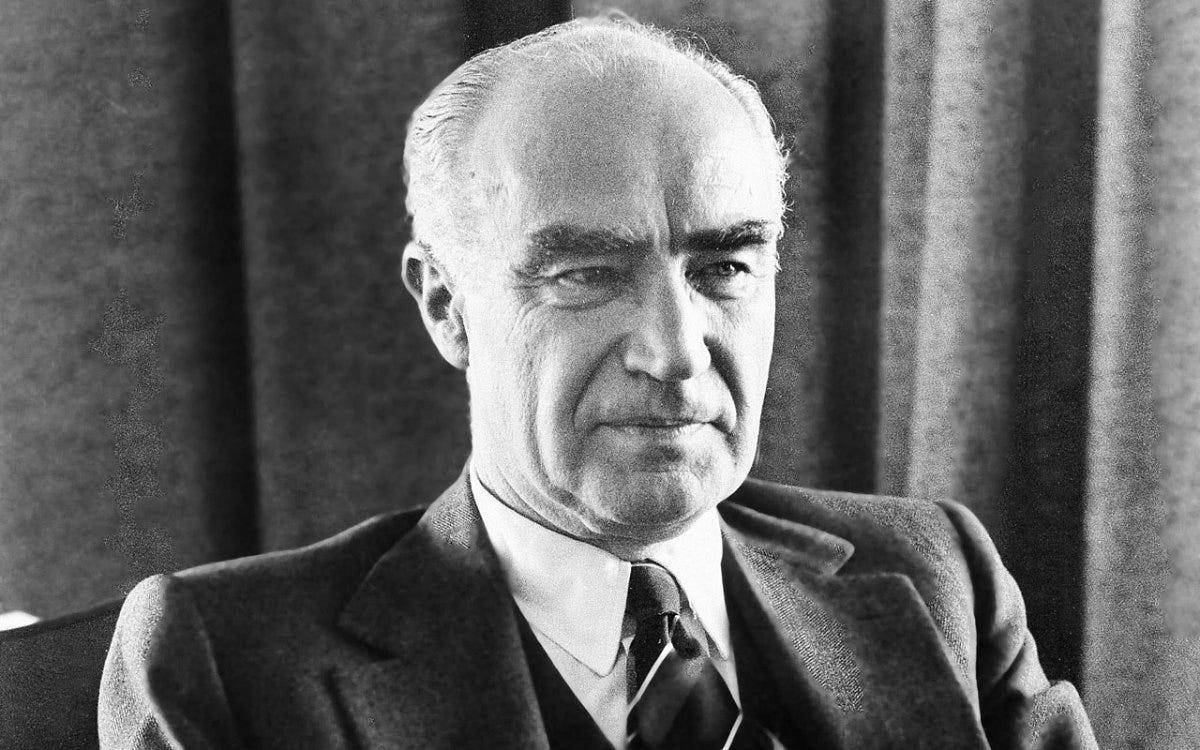

In the mid-20th century, “conservative” media magnate Henry Robinson Luce, publisher of Time and Life magazines, surprisingly expressed a fascination with LSD and psychedelic experiences. Despite Time Inc.'s corporate culture being more reminiscent of "Mad Men," known for its alcohol-fueled celebrations, Luce's interest in mind-altering substances became apparent. At a memorable gathering in 1964, Luce announced to his staff that he and his wife, Clare Boothe Luce, had experimented with LSD under doctor's supervision. This unexpected revelation contrasted with his conventional lifestyle and political conservatism, highlighting an unusual intrigue with psychedelics within Luce's influential media sphere during the 1950s and 60s.

“I’ve always maintained that Henry Luce did more to popularize acid than Timothy Leary,” wrote the 1960s provocateur Abbie Hoffman, “just about the time a Life magazine cover story was touting LSD as the new wonder drug that would end aggression.”

The image of Luce as a simple “publisher” is instantly dispelled under the most cursory examination. Luce could be considered the father of mainstream media, an iconic figure in 20th-century American journalism and the influential driving force behind the creation of Time, Life, Fortune, and Sports Illustrated magazines. Born in 1898 in Shandong, China, to Presbyterian missionaries, Luce spent his formative years in the United States, eventually graduating from Yale and carving a path that would revolutionize the way America consumed news. His groundbreaking vision birthed the first multimedia corporation, changing not only the landscape of journalism but also the reading habits of millions of Americans.

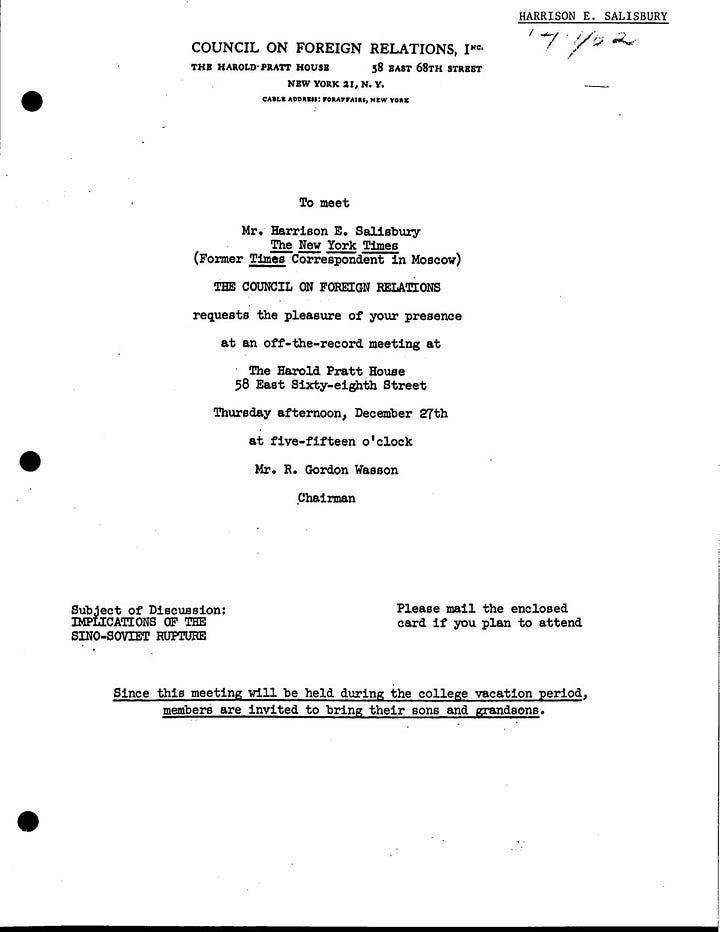

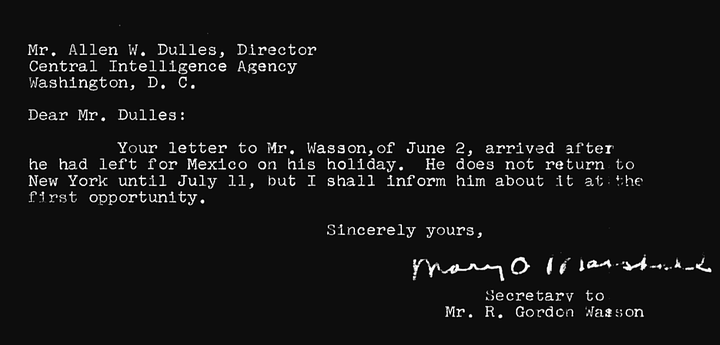

Yet Luce's impact was not limited to the realm of media. As a significant player in American politics, he utilized his expansive media empire to influence public sentiment and shape foreign policy. A dedicated Republican and a key figure in the "China Lobby", Luce's sway extended into America's intelligence community. His close friendship with Allen Dulles, a notable CIA operative, facilitated the intertwining of Time Inc. and the CIA in a cooperative relationship. Luce's media outlets offered the perfect cover for CIA agents, allowing the agency to embed itself in the world of journalism and, in turn, subtly steer public discourse. Luce's legacy therefore embodies not only the transformation of American media but also highlights the intricate and often invisible ties between media, politics, and intelligence services.

Not only was he a “bonesman,” but his membership in the secret society was instrumental in founding his media empire:

In the summer of 1922, Hadden and his cousin John S. Martin sought still more underwriters by visiting country clubs from New York to Chicago in Martin’s new roadster. Yale associates in these new upper-class enclaves welcomed them with open arms and thousand-dollar investments. Having belonged to Yale’s exclusive Skull and Bones aided them all the more, as that connection led Luce and Hadden to the home of Mrs. William L. Harkness of New York and their largest single catch, twenty thousand dollars. Although short of their hundred-thousand-dollar goal, the young men now had enough— eighty-six thousand dollars—for Time to begin.

-Henry R. Luce and the rise of the American news media by Baughman, James

Referred to as Baal3 by his fellow bonesmen, Luce was deeply embroiled in Operation Mockingbird.4 Documents from the CIA and Senate suggest that the CIA maintained written agreements with foreign correspondents from Time and Newsweek. Allen Dulles maintained frequent communication with Luce, who, in turn, provided the agency with access to his staff. Luce also facilitated cover for CIA agents by offering them Time-Life credentials.