Poltergeist

The Crisis of Civility in the Shadow Realm

Photographs have the kind of authority over imagination to-day, which the printed word had yesterday, and the spoken word before that.

—Walter Lippmann

Imagination is the star in man, the celestial or super-celestial body.

—Carl Jung

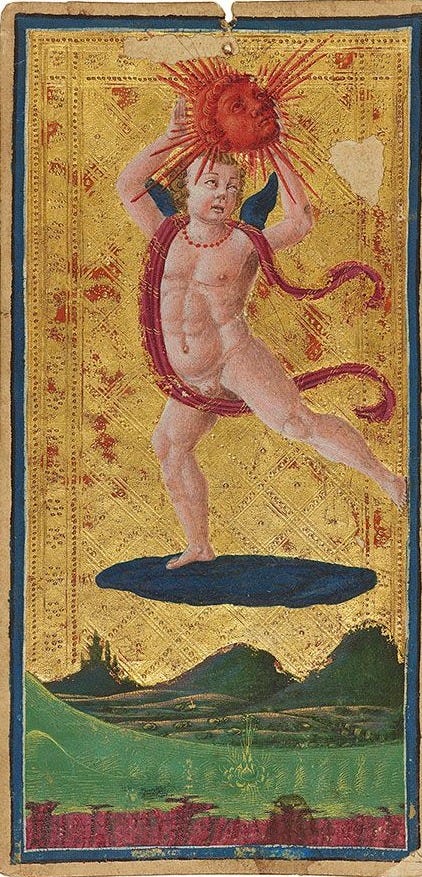

You are hallucinating. Half of what you see springs from your own store of images. In every scene, your perceptual system executes a kill chain: judgments are made, visual information is eliminated—in milliseconds. The noble eye flenses the raw spectrum of visual data. Everywhere, you perceive a collage of fact and fiction. All this carnage is pre-rational, non-verbal, unconscious. The mind's eye mirrors this process in metacognition. Even you—your consciousness—is a phantom of real and supernal images, a projection of metals, mercury, and salt, dissolved and reformed in an unknown star. You have never touched a material world, bur only the smoke of God, a chiasmus of matter and images spilling into the eye, making dead vision resort to life.

The artist, architect, engineer and weapons expert of Ludovico Sforza and Cesare Borgia grasped well the power of the image. Considered the proto-architect of military technology, Leonardo da Vinci was essentially a court wizard who designed and deployed programmable robots, tanks, and multi-barreled cannon systems, yet he said that through the image, “lovers are moved to speak to the figure of the beloved object; through them, the people are stirred to seek with fervent vows the images of the gods; this is not done by the sight of works of poets who might present those same gods with words.” (da Vinci 1909).

The image enters through the noblest sense, Sight, as a simultaneous, concentrated harmony that serves the eye in a moment of time. Da Vinci contends that it is only the image which evokes religious fervor, and not the words of poets. The image rules this world, “and through them (even) animals are deceived. I have seen a painting that deceived a dog by the appearance of its master, and the dog showed it great joy and honor; likewise, I saw how dogs barked and wanted to bite at painted dogs, and I saw a monkey engage in endless follies against another, painted monkey. I have seen how swallows flew up and wanted to settle on painted iron bars” (da Vinci 1909). Not only is the dog and monkey deceived, but also man’s innocent heart. He speaks, with pride in his warrior art, of poor souls falling in love with paintings,

And if the poet says that he can inflame men with love, which is a principal thing among all animated beings, the painter has the power to do the same, and more so, since he places the image of the beloved before the lover; and often the lover kisses this image and speaks to it, which he would not do were the same beauties represented by the writer; still better, the painter so affects the minds of men that they fall in love and come to love a painting that does not represent any living woman. And it happened to me that I made a picture with a religious subject that was bought by a lover who wished to have the divine attributes removed so that he could kiss it without scruples ; but at last conscience overcame sighs and desire, and he had to remove the image from his house.

Traktat von der Malerei, by Leonardo da Vinci (1909) (emphasis mine)

Da Vinci is compelled to note this innovation, this technology for making men fall in love with women who don’t exist. If the Image-maker wants to summon beauties that drive man to love, he is master over bringing them into existence, and if he wants the people to see things monstrous, frightening, or comical and laughable, the engineer of the Image is master and god over them. Thus, the warrior-artist enters the chamber of images and makes his dominion there.

In Public Opinion, Walter Lippmann gives the example of an experiment demonstrated at a psychology congress in Göttingen, which showed how stereotypes (fixed images) distort perception. During a staged incident, a clown and a masked man enacted a brief fight. Forty trained observers were asked to write reports immediately. Only one report contained less than 20% errors, while most had between 20% to over 50% inaccuracies. Many reports included details that were pure invention. The observers, instead of accurately recalling the scene, projected stereotypes of similar brawls they had encountered in their lives.

Thus out of forty trained observers writing a responsible account of a scene that had just happened before their eyes, more than a majority saw a scene that had not taken place. What then did they see? One would suppose it was easier to tell what had occurred, than to invent something which had not occurred. They saw their stereotype of such a brawl. All of them had in the course of their lives acquired a series of images of brawls, and these images flickered before their eyes. In one man these images displaced less than 20% of the actual scene, in thirteen men more than half. In thirty-four out of the forty observers the stereotypes preempted at least one-tenth of the scene

—Public Opinion, Walter Lippmann

Lippmann was the first to plainly state, in a way that could be cleanly integrated into the social sciences, “We do not first see, and then define, we define first and then see. In the great blooming, buzzing confusion of the outer world, we pick out what our culture has already defined for us, and we tend to perceive that which we have picked out in the form stereotyped for us by our culture.” (Lippmann 1922)

In his chapter Stereotypes, Lippmann repeatedly uses the painting to illustrate his points, he speaks of the displeasure when a painter “does not visualize objects exactly as we do,” and how our difficulty in appreciating medieval art arises because “our manner of visualizing forms has changed in a thousand ways.” He describes how the human figure, as shaped by Donatello and Masaccio, became a new standard: “People had perforce to see things in that way and in no other, and to see only the shapes depicted, to love only the ideals presented.”

He comments on the “strange connection” between our vision and the facts. A man might rarely look at a landscape except to consider its division into building lots, but he has seen landscapes hanging in parlors. “From them, he has learned to think of a landscape as a rosy sunset, or as a country road with a church steeple and a silver moon.” When he goes to the country, he may not notice any landscape until the sun sets rosy, at which point he recognizes it as a “landscape” and exclaims that it is beautiful.

Yet when he tries to recall it, “the odds are that he will remember chiefly some landscape in a parlor.” He did see a sunset, “but he saw in it, and above all remembers from it, more of what the oil painting taught him to observe” than what an impressionist painter or a Japanese artist might have seen.

“In untrained observation, we pick recognizable signs out of the environment. The signs stand for ideas, and these ideas we fill out with our stock of images. We do not so much see this man and that sunset; rather we notice that the thing is man or sunset, and then see chiefly what our mind is already full of on those subjects.”

The effort to see all things freshly and in detail is exhausting and impractical in busy lives. Classification is necessary, yet “we feel intuitively that all classification is in relation to some purpose not necessarily our own.” The most subtle and pervasive influences are those that establish and sustain these stereotypes, leading us to imagine much of the world before we actually experience it.

Lippmann's observation that "types acquired through fiction tend to be imposed on reality" anticipates Baudrillard's Simulacra and Simulation. His reflection on the influence of the cinema, where the moving picture "steadily builds up imagery... then evoked by the words people read," will be echoed by Baudrillard more than half a century later: “Every day the media pretend to make the masses speak, but in reality they only reaffirm their own self-referentiality.”

Lippmann anticipates concepts like the autopoietic and self-referential hyperreality, by coining the term "pseudo-environment." This pseudo-environment feeds the shadows of Plato's cave, mediating between the individual and the environment. Humans reconstruct reality through narratives, often using unconscious images or previous experiences. Fiction, for Lippmann, is not a lie but "a representation of the environment fabricated by humans themselves" (Lippmann 1922). Public Opinion regards the stereotype as inevitable and natural, because "we are not equipped to deal with so much subtlety, so much variety, so many permutations and combinations," all the blooming and buzzing which confront us in the mediasphere,

”And those preconceptions, unless education has made us acutely aware, govern deeply the whole process of perception. They mark out certain objects as familiar or strange, emphasizing the difference, so that the slightly familiar is seen as very familiar, and the somewhat strange as sharply alien. They are aroused by small signs, which may vary from a true index to a vague analogy. Aroused, they flood fresh vision with older images, and project into the world what has been resurrected in memory. Were there no practical uniformities in the environment, there would be no economy and only error in the human habit of accepting foresight for sight. But there are uniformities sufficiently accurate, and the need of economizing attention is so inevitable, that the abandonment of all stereotypes for a wholly innocent approach to experience would impoverish human life.” (Lippmann 1922)

Bridgerton Poltergeist

I was buried alive in a void which was the wound that had been dealt me. I was the wound itself.

—Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn (1939)

The example of the Bridgerton Poltergeist illustrates the consequences of disregarding a single, longstanding stereotype—the "demon"—which has faithfully served humanity since ancient times in every civilization prior to the modern era. When such a functional stereotype is deliberately excised by managerial decree, the resulting void, the perceptual wound, may come to define one’s entire reality.

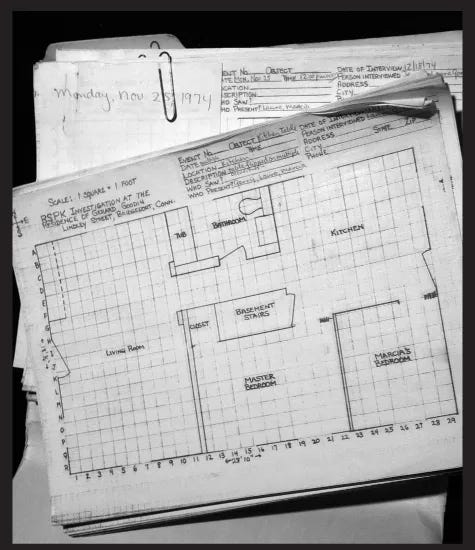

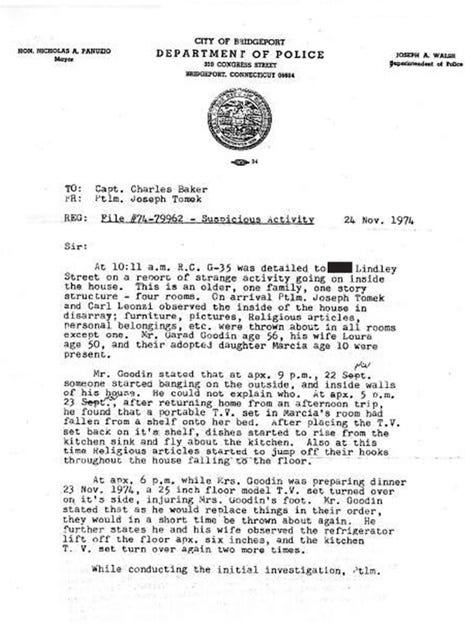

The Bridgeport Poltergeist case involves the Goodins family—Jerry, Laura, and their adopted daughter Marcia—in a small bungalow on Lindley Street, Connecticut. After adopting Marcia in May 1968, the family began experiencing unexplained phenomena, including moving objects, loud banging noises, and eerie footprints. On the night of November 21, 1974, these activities climaxed, attracting police involvement and the attention of renowned paranormal investigators Ed and Lorraine Warren. Multiple police officers, firefighters and neighbors reported witnessing the strange phenomena, such as televisions falling, refrigerators sliding, and furniture moving on its own. Attesting to the credibility of the four officers first to arrive, Lieutenant Leonard Coco stated, “Together they have more than 100 years of experience. If they said they saw something, they saw something. I just don’t know what it was.”

Despite an abundance of credible eyewitness accounts, the lead investigator Philip Clark ultimately declared the case a hoax, suggesting that Marcia (a 10-year-old Native American orphan weighing 70 pounds in the full view of policemen and firemen) was responsible for the events. The Goodins disputed these claims, alleging manipulation by investigators. Over the years, the controversy persisted, with ongoing reports of paranormal activity and public skepticism. The family's struggle to sell their home due to its haunted reputation continued until their eventual deaths, leaving the Bridgeport Poltergeist case as one of the most documented paranormal cases on record. Unsurprisingly, despite national media coverage, the case has no Wikipedia page nor mention on paranormal investigators Ed and Lorraine Warren’s entry.

Subject haunted house:

Sir:

While I am patrolling in car 823, my partner and I went to Lindley Street to cover G-35. Upon entering the house I saw a picture fall off from the wall, a small desk moved and a clock on the kitchen shelf fell. I immediately left the house and waited outside for my partner.

Respectfully submitted,

Patrolman Leroy Lawson

Before the night of November 21, the Goodin family experienced a range of unusual phenomena in their bungalow. They noticed objects mysteriously disappearing and reappearing in different locations, persistent pounding noises that sounded like rocks hitting the walls, and wet footprints appearing on their dry porch. Doors and windows would open and close by themselves, while furniture such as chairs and sofas would shift positions or even float without any visible force. Marcia, their adopted daughter, exhibited unusual behavior by talking to her teddy bears, claiming to converse with an unseen grandfather. Additionally, household items like televisions and refrigerators moved or fell inexplicably, curtains rolled up on their own, and sudden temperature drops occurred in various rooms accompanied by the occasional smell of sulfur. Friends, neighbors, and visitors, including children like Rosemarie Hoffman, also witnessed these strange occurrences, heightening the family's fear and suspicion of a malevolent presence in their home.

This went on for six years. It was nearly two years before they even considered something supernatural was happening, and it was not until every room in their house was shredded to pieces that Jerry Goodins calls the police. Only then is he able to define his reality, telling Officer John Holsworth, "There's some kind of evil force wrecking our home."

The Shadow Realm of Modernity

In the course of the nineteenth century society was personified under the influence largely of the nationalist and the socialist movements. Each of these doctrinal influences in its own way insisted upon treating the public as the agent of an overmastering social purpose. In point of fact, the real agents were the nationalist leaders and their lieutenants, the social reformers and their lieutenants. But they moved behind a veil of imagery.

—The Phantom Public, Walter Lippmann

In The Phantom Public, Lippmann deepens his analysis of public relations by portraying the public as passive "spectators" of a reality crafted by elites and mediated through media representations. This artificial environment, the "pseudo-environment," is a space in which external forces, such as the media and socio-cultural engineers, manufacture the narratives people rely on to interpret the world. This frame recognizes the masses as "phantoms," spectators of their own political and social realities, disengaged from meaningful agency. As Lippmann notes, "this public is a mere phantom. It is an abstraction," there is no fixed public but only instanced “random publics” composed of individuals who may be momentarily, and perhaps violently concerned with an issue but lack the sustained attention, or coherent principles, to follow that issue beyond choosing a favored actor in any given scene.

Baudrillard famously takes Lippmann’s notion of pseudo-environments further by arguing that, in contemporary society, images no longer merely distort reality—they replace it altogether. In Simulacra and Simulation, Baudrillard writes of a hyper-real world in which representations have become self-referential and detached from any original source. This marks the collapse of the distinction between the real and the constructed, leaving the public to consume simulacra as if they were reality itself, ripping a wound in the deepest dimensions of human experience.

Baudrillard’s notion of the "black hole" of the masses, articulated in All'ombra delle maggioranze silenziose, mirrors Lippmann's idea that mass man is only able to engage superficially with political and social issues, merely absorbing information without contributing meaningfully to discourse. The public, like Lippmann's "raw material of government," is shaped and directed by those in power. The phantom public sphere hosts “neither hysteria nor potential fascism, but simulation by precipitation of all lost referents. (…) A black box of all uncaptured meanings. The mass is what remains when the social has been forgotten” (Braudillard 1978a: 29).

Arguably Lippmann’s greatest influence, the parapsychologist William James instilled in him a deep respect for pragmatism, skepticism of dogma, and a focus on empirical experience. In fact, Lippmann pragmatized James’s concepts of subjective experience, formulated as "pictures in their heads" which act as psychological and cultural filters . This idea of mediated perception greatly informed Lippmann's concept of the "pseudo-environment.” In Public Opinion’s chapter on the Stereotype Lippmann writes “An unfamiliar scene is like the baby’s world, ‘one great, blooming, buzzing confusion,” directly quoting James’ Principles of Psychology.

In The Principles of Psychology (1890), William James outlines the concept of the image as both a psychological and perceptual phenomenon. He discusses how, through experience and repetition, certain parts of an image become more vivid and are more readily reproduced by the nervous system. This process leads to 'complementary reproduction,' where our brain fills in missing parts of an image based on previous experiences, allowing us to perceive things that might not be physically present in the stimulus. James explains that this happens, for instance, when 'a few points and disconnected strokes are sufficient to make us see a human face'. These images are not merely visual impressions but also 'sensations' grounded in our nervous system's history of interactions with similar images.

The scheme of relations invoked by images extend at both ends of the spectrum, into the subliminal and the suprasensory world,

The imagination, imagery, and the paranormal go hand in hand. They are found together in mystical traditions stretching back millennia, in long occult traditions, and in scientific parapsychology. Ghosts, demons, angels, spirits, visionary experience, and altered states of consciousness all involve imagery… Hypnosis can produce hallucinations and has also been used to facilitate ESP. Parapsychologists have demonstrated that dreams, ganzfeld, and other methods that alter consciousness and stimulate imagery also enhance ESP receptiveness…. The existence of psi suggests that imagination and reality are not clearly separable. This is a disconcerting idea, but it must be explored if one wishes to understand the paranormal. The binary oppositions of internal-external, subjective-objective, fantasy-reality are fundamental to the Western worldview, and anything that proposes a blurring of them is dismissed as irrational. Yet psi engages both the mental and physical worlds, both the imagination and reality; there is an interface, an interaction.

—The Trickster and the Paranormal, George Hansen

James was deeply fascinated by psychic phenomena, his empirical research focused on "extraordinary subjective experience," "supraconscious processes," and the subjective transcendental experience. In 1869, he reviewed a book on spiritualism, calling it a subject of “transcendent interest,” stating, “if once admitted,…must make a great revolution in our conception of the physical universe” (James, 1869). His involvement with the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) began in 1883, investigating all sorts of supernatural matters including mediums, clairvoyants, apparitions, haunted houses, and hypnosis.

In 1884, James helped establish the American branch of the SPR, later merging with the British society, where he served as vice president and later president. James took an active research role, contributing reports on spiritualism, apparitions, and hauntings. He worked extensively with the Committee on Hypnosis, using Harvard students as subjects (Richardson, 2006, p. 270). He attributed the discovery of the "subliminal consciousness" to F. W. H. Myers, who coined the term "telepathy" and explored life after death. Myers’ work in Phantasms of the Living documented over 700 cases of apparitions, “crisis hallucinations,” and telepathic communication, linking these phenomena to potential evidence of postmortem survival. James consistently contributed to the SPR journal, investigating mediumship, trance states, and the broader potential of the human mind. In his essay “The Confidences of a ‘Psychical Researcher,’” written shortly before his death, James admitted that his investigations had not yielded definitive answers. Ghosts, he concluded, neither exist nor do not exist, leaving him with what he called a “perpetual bafflement.” Elsewhere,

This “bafflement” aligns perfectly with the Trickster paradigm. Ghosts are liminal—interstitial—beings who dwell in the netherworld between life and death, challenging the notion of a clear boundary between the two.

ESP and PK are, by definition, boundary crossing. They surmount the barriers between mind and mind (telepathy), mind and matter (clairvoyance and PK), as well as the limitations of time (precognition), and that of life and death (spirit mediumship, ghosts, and reincarnation). Likewise, magic tricks violate our expectations of what is and is not possible, and the relationship between psi and trickery is far deeper than most have assumed. Psi blurs distinctions between imagination and reality, between subjective and objective, between signifier and signified, between internal and external. The same is true in much deception. Studies of animals show that pretense (i.e., pretending) is often required for deceit, and pretense blurs the distinction between imagination and reality. Blurring of fantasy and reality occurs with nonrational beliefs pervasive in religion and myth as well as in good fiction.

—The Trickster and the Paranormal, George Hansen

James immersed himself in countless séances, particularly with the famed medium Leonora Piper, whom he esteemed as profoundly significant. Of Mrs. Piper, he penned, "She can at will descend into a trance state, wherein she is 'possessed' by a power purporting to be the spirit of a French doctor, serving as the bridge between the sitter and their departed kin."

Through multiple sessions with her, James concluded that Piper's trance states were genuine and that she possessed unexplained abilities. Between 1885 and 1886, he meticulously chronicled about twenty-four sittings, employing aliases to veil the identities of the sitters, thus ensuring rigorous conditions. Despite his initial skepticism, he became convinced that Piper's gifts could not be dismissed as mere trickery. By 1896, James famously dubbed her his "white crow," implying that while most mediums were fraudulent, Piper's phenomena were authentic enough to unsettle the prevailing scientific doctrines. He frames himself as the reluctant believer, saying he could not “resist the conviction that knowledge appears which she has never gained by the ordinary use of her eyes and ears and wits’’ (James, 1896)

His conclusions were cautious, he recommended that the American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR) study her under controlled conditions to amass systematic evidence. Leonora Piper's mediumship diverged from that of most mediums; her abilities were rooted in psychoid phenomena, focusing on spectral dialogues and script rather than dramatic paraphysical acts like table-rapping or levitation. Controlled by the enigmatic entity called "Dr. Phinuit," Piper's trances allowed for systematic scrutiny, with stenographic records making it easier to dissect the messages conveyed.

James orchestrated unique experiments with Piper that revealed physiological divergences between trance states and other altered states like hypnosis. In one eerie instance, he made a slight incision on Piper's wrist while she was entranced; though no blood seeped during the trance, the wound bled immediately upon her awakening. This uncanny phenomenon suggested a profound disunion between her mental and corporeal realms, not typically observed in hypnotic subjects.

Moreover, James expressed an openness to forces "not yet dreamed of in philosophy," willing to entertain notions neither strictly material nor purely spiritual but dwelling somewhere in between. He referred to this as a "tertium quid," a third essence, rejecting both traditional materialism and spiritualism. His psychical research ultimately nourished his broader metaphysical musings, including his theory of immortality, which he envisioned as a "sublime reservoir" where traces of individual consciousness might linger beyond the grave. James suggested that consciousness could merge into a larger cosmic consciousness while retaining some semblance of individuality. This conception of a "mother sea of consciousness" was inspired by his explorations into trance states and other spectral phenomena.

In 1892, William James developed his theory of the subliminal self, suggesting that trance states in mental mediums, like those he observed in Mrs. Piper, demonstrated the existence of "extra-consciousness". This expanded his earlier discussions of mental life as a series of “strata of consciousness”. He posited the simultaneous existence of “two different strata of consciousness”, which were unaware of each other, a view that diverged from earlier binary models of conscious and unconscious states.

James also introduced several key terms to explain these layers: “below the threshold”, “above the threshold”, “subconscious mental operations”, and the now well-known "beyond the margin" of consciousness. Through these concepts, he framed the unconscious as an entity, rather than just descriptive mental states, moving beyond a simple upstairs-downstairs model. This model suggested that our ordinary waking consciousness is but a small part of a much larger hidden self, which he named the subliminal self. James described this as a vast reservoir of memories and abilities, which can influence the conscious mind through eruptions into our ordinary awareness.

James emphasized the fluidity of these hidden layers, explaining that the subliminal self played an integral role in everyday life. He remarked, “We all have potentially a ‘subliminal self,’ which may make at any time irruption into our ordinary lives. In its lowest phases it is only the depository of our forgotten memories; in its highest, we don’t know what it is at all. . . . Whatever it is, it is subconscious.”

James believed that the subliminal self could emerge into conscious awareness in various ways, such as through trance states, automatic writing, or mediumistic experiences. He proposed that human consciousness was not unified but split into different strata, each with its own thoughts, feelings, and memories. His idea of the subliminal self suggested that unconscious processes were not merely passive or pathological but could actively influence behavior and perception.

William James and Frederic Myers both worked to unveil the enigma of "hidden selves," exploring how the mind is cleft between the "supraliminal" and the "subliminal." Myers coined the term "subliminal self" to denote the shadowy realm of unconscious mental activity that lies beyond the bounds of ordinary consciousness—a pivotal idea influenced by James's own psychological theories, particularly his "stream of consciousness" model. Myers argued that the mind is layered like a labyrinth, with the supraliminal consciousness merely the facade visible in daily awareness, while the subliminal depths harbor forgotten memories, creativity, and even the eerie potential for telepathic powers.

Myers expanded upon this with his theory of human personality, wherein the subliminal was not just a passive reservoir but an active, intricate entity. He described it as a "Self" capable of orchestrating memories and ushering forth psychic experiences such as clairvoyance and telepathy. Myers's framework suggested that these hidden "selves" could occasionally breach the walls of consciousness, resulting in phenomena like automatic writing and dissociative states.

Frederic Myers, who introduced this concept of the "subliminal self" in his essays between 1892 and 1895, further developed these toward his major work, Human Personality and Its Survival of Bodily Death, published posthumously in 1903. His essays underpinned the book, which delved into various psychical phenomena to theorize about the entire human psyche. Myers was motivated by the question of whether a person's personality survives death. His book sought to provide a well-researched answer, using his psychical research—the study of genius, sleep, hypnotism, sensory automatism, phantasms of the dead, motor automatism, trance, possession, and ecstatic states—to reconcile science and religion.

Myers aimed to demonstrate the existence of unexpressed mental states and show they were not pathological, but existed in all healthy minds, an idea that even James found compelling and cited in his own work. Myers wrote, "Each of us is in reality an abiding psychical entity far more extensive than he knows—an individuality which can never express itself completely through any corporeal manifestation. The Self manifests itself through the organism; but there is always some part of the Self unmanifested; and always . . . some power of organic expression in abeyance or in reserve.” Myers firmly believed our consciousness is just a fraction of mental life:

All this psychical action, I hold is conscious; all is included in an actual or potential memory below the threshold of our habitual consciousness. For all which lies below that threshold subliminal seems the fittest word. “Unconscious,” or even “subconscious,” would be directly misleading; and to speak . . . of the secondary self may give the impression either that there cannot be more selves than two, or that the supraliminal self, the self above the threshold,—the empirical self, the self of common experience—is in some way superior to other possible selves. . . . I hold . . . that this subliminal consciousness and subliminal memory may embrace a far wider range both of physiological and of psychical activity than is open to our supraliminal consciousness, [and] to our supraliminal memory. The spectrum of consciousness, if I may so call it, is the subliminal self indefinitely extended at both ends.

—The Subliminal Self, by Frederic W. H. Myers

If this all sounds familiar, that is because Walter Lippmann wasn’t the only one indebted to this axis,

[O]ur view of the historical Jung has been heavily compromised by non- or anti-Jungian ideologies as well. Even today, Jung is usually seen primarily from the perspective of his relation to Freud, and the dominant “Freud legend” has pictured him as the renegade student who abandoned psychoanalysis for a speculative worldview more akin to mysticism than to science. In fact, however, Jung was indebted at least as much, and arguably more, to the tradition of William James, Frederic Myers, and his Swiss compatriot Theodore Flournoy.

—Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture, by Wouter J. Hanegraaff, Universiteit van Amsterdam

Jung advanced modern psychology by revising the concept of the archetype and its relation to the drive, using a spectrum analogy: “the dynamism of the drive is lodged as it were in the infra-red part of the spectrum, the image of the drive lies in the ultra-violet part” (§ 414, trans. mod.). He posited that drives have dual aspects—experienced physiologically and entering consciousness as images.

Echoing Myers, Jung maintained that the spectrum of consciousness extended “at the red end into the deeps of organic life, and at the violet end into a world of suprasensory perceptions” (Jung 1892, 483) Drives remained unassimilated at the red end of the spectrum, but their images could be integrated at the violet end, enabling analysis to transform instincts through image mediation. Jung extensively revised his concept of the unconscious, referencing James’ recognition of an extra-marginal realm of consciousness and Frederic Myers’ notion of the subliminal consciousness, which also used the spectrum analogy:

“At the inferior, or physiological end . . . it includes much that is too archaic, too rudimentary, to be retained in the supraliminal memory . . . at the superior or psychical end, the subliminal memory includes an unknown category of impressions which the supraliminal consciousness is incapable of receiving in any direct fashion, and which it must cognize, if at all, in the shape of messages from the subliminal consciousness” (Myers 1891, 306).

As Sonu Shamdasani notes in Jung and the making of Modern Psychology, “The closeness of Myers’ spectrum analogy to Jung’s suggests that if Jung did not draw it directly from Myers, it forms a striking example of cryptomnesia.” Jung observed that both conscious and unconscious contents function similarly, leading to the paradox that no content is entirely conscious or unconscious. Everything wakes and sleeps. To address this, he proposed the unconscious as a “multiple consciousness,” characterized by a “consciousness-like state of unconscious contents” and alchemical symbols. In other words, a spectrum of selves “In this reformulation of the unconscious, Jung was aligning it far more closely with Frederic Myers’ conception of the subliminal consciousness and William James’ conception of the transmarginal field” (Shamdasani 2003).

The work of Eugene Taylor makes paramount the influence of Swiss parapsychologist Théodore Flournoy and locates Jung as part of a French-Swiss-English-American axis with Frederick Myers and William James representing England and America. (Taylor 1998). Jung valued scientific objectivity in his work, a rigor he learned from the Jamesian pragmatist Flournoy, a psychical researcher who also conducted medium experiments and shared William James's views on subjects like parapsychology and the science of religions.

Before meeting James, Jung absorbed his philosophy through Flournoy, and he noted the two men were alike in their attitude of psychic objectivity and clarity within a "very broad framework." Jung felt secure in his mentorship with both men, appreciating the sense of mutuality and "equality" they shared. In his 1936 Harvard lecture, Jung reflected on James, stating: “It was [James’s] far-ranging mind which made me realize that the horizons of human psychology widen into the immeasurable.” (Hermann 2020)

Jung asserted, “Every psychic process is an image and an imagining” (CW 6, § 77), In Western alchemy, which greatly influenced Jung's later thoughts on the psyche, imaginatio was crucial. Alchemists believed that the opus, or great work, required “true imagination.” These imaginal phenomena belonged to “an intermediate realm between mind and matter… a psychic realm of subtle bodies” that could manifest in both mental and material forms (CW 12, § 394). Jung, who had his own experience of the numinous—including compound hallucinations of Philemon, hyperphantasiac projections, hypnagogic-hypnopompic interactions with spirits, and at least one account of a time slip—puts the Image at the center of his psychology,

”It is my mind, with its store of images, that gives the world colour and sound; and…“experience” is, in its most simple form, an exceedingly complicated structure of mental images. Thus there is in a certain sense nothing that is directly experienced except the mind itself. So thick and deceptive is this fog about us that we had to invent the exact sciences in order to catch at least a glimmer of the so-called “real” nature of things. (Jung 1926)

Much of the more “occult” work of William James and Frederic Myers can only be found by looking in the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR). In James’ case, much of his writing was only published for a restricted SPR-associated audience and would not republished for more than half a century after his death. In fact, certain key lectures were never published at all. We know that “Jung enthusiastically engaged James in discussions about parapsychology” (Ryan 2008), and with the SPR journal we find Myers repeatedly discussing the role of images transmitting information from the “subliminal self” as early as 1893, corresponding closely to Jung’s vision of the unconscious. Here is but one example:

”I maintain that visual knowledge, both of the material world and of what we at present call immaterial relations, is in fact attainable through visions which I term automatic, as being neither evoked nor evocable by the supraliminal self, but which, as I hold, have their origin (or proximate origin) in the subliminal self, and carry up its messages into our current and familiar conscious¬ ness. I of course admit that in some cases these messages merely indicate disease and disintegration; and that in most cases they are meaningless, fragmentary, or abortive. But I claim that in some crises they convey real knowledge, acquired by some perceptivity which is possessed only by the subliminal and not by the supraliminal self.”

—Frederic W. H. Myers, The Subliminal Self

Myers based his argument for the existence of the Subliminal Self on British psychical research. He cited twenty years of data from the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) on hypnotism, particularly the work of Frank Podmore, founder of the Fabian Society, as presented in Phantasms of the Living (1886), which he believed demonstrated the truth of telepathy. Along with subsequent work with Spiritualist mediums like Mrs. Leonora Piper, he used this research to make his case, providing evidence for the dominance of subliminal life:

She presents an instance of automatism of the extreme type where the “possession” is not merely local or partial, but affects, so to say, the whole psychical area,—where the subliminal self is for a time completely displaced, and the whole personality appears to suffer intermittent change. In other words, she passes into a trance, during which her organs of speech or writing are “controlled” by other personalities than the normal waking one. Occasionally, either just before or just after the trance, the subliminal self appears to take some control of the organism for a brief interval; but with this exception the personalities that speak or write during her trance claim to be discarnate.

Human Personality, Myers, 327

In conclusion, the “Freudocentric Legend” of Jung is a hoax. In reality, there are about one or two degrees of separation between Jung's concept of the unconscious and the world of mediums, hauntings, cutting witches to see if they bleed, and a demon called "Dr. Phinuit" studied by the Society for Psychical Research. This is not to say that Jung is corrupted by this; on the contrary, this is the résumé of a true alchemo-shaman.

Reading Jung directly and tracing his axes of influence really drives home that it isn’t so much about the “suppression” of occult origins, but rather the “hylic impulse” to grab something, slap a mundane coat of paint on it, and resell it to the public in a diluted, rootless form.

Of course, suppression comes later, after the empty skinsuits succeed in gaining influence and “professionalizing.” But this is done mostly by academic dung beetles and other wretched parasites. To maintain prestige, half of their energies are devoted to covering up grabby little tracks. This process, which we find everywhere in the social sciences, should be considered the main cause of “stuck science.”

In your research, did you ever come across parapsychologist or paranormal researchers (like James and Jung) interviewing Catholic or Eastern Orthodox mystics or priests?

The reason I ask is because, it may be an untapped area of research. In the Eastern Orthodox tradition there are accounts of levitating, clairvoyance, and other miracles healings as well… (in the 20th century!)

If the “demon” card/stereotype is an example of a card excised from the deck is there an example of a counterfeit card/mediated stereotype that has been inserted into the deck. What is worse: to not have a full deck or to have a corrupted deck. This reminds me of Camille Paglia ( herself an atheist) chiding militant atheist on attempting to take away religion from the young and giving them nothing to replace it.