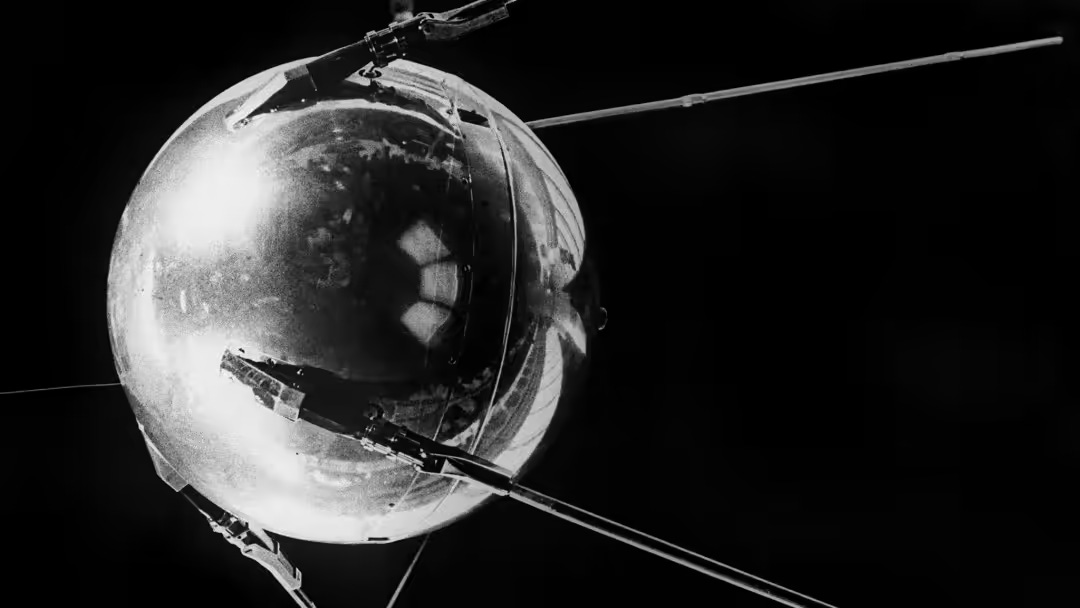

The genesis of DARPA dates back to the launch of Sputnik, its mission was framed as a commitment by the United States to be the initiator, and not the victim, of future technological surprise. President Dwight Eisenhower created the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) to address US technological research and development needs as a response to the Soviet Union's launch of this first orbiting satellite on October 4th 1957.

To understand the nature of this historic mobilization, the first thing to note is that Sputnik was in no way a surprise. In 1958, science writer, Willy Ley catalogued a number of news reports communicating that the Soviets were about to launch a satellite—

“If somebody tells me that he has the rockets to shoot — which we know from other sources, anyway — and tells me what he will shoot, how he will shoot it, and in general says virtually everything except for the precise date — well, what should I feel like if I’m surprised when the man shoots?”

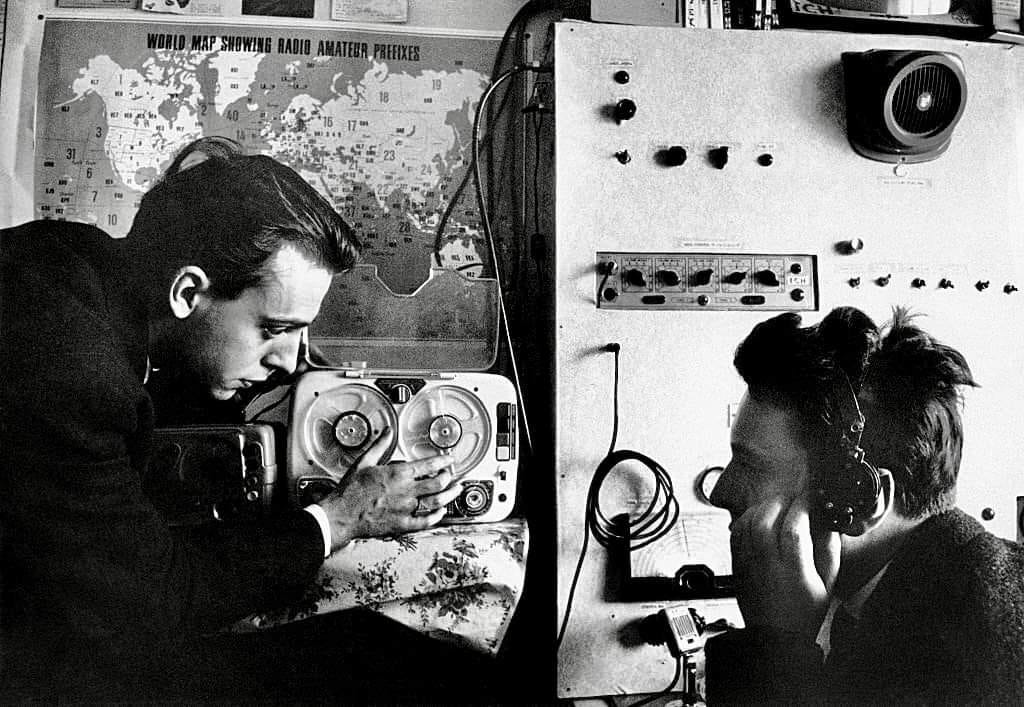

Ley's investigation revealed that, around the middle of September 1957--two weeks before the announcement of the "new moon"--radio hams in Portland had received word from their Japanese counterparts that the Soviet government had already released Sputnik's telemetry and frequency data to Japanese radio amateurs and "moonwatchers", allowing them to prepare their receiving equipment and tune in for the imminent launch.

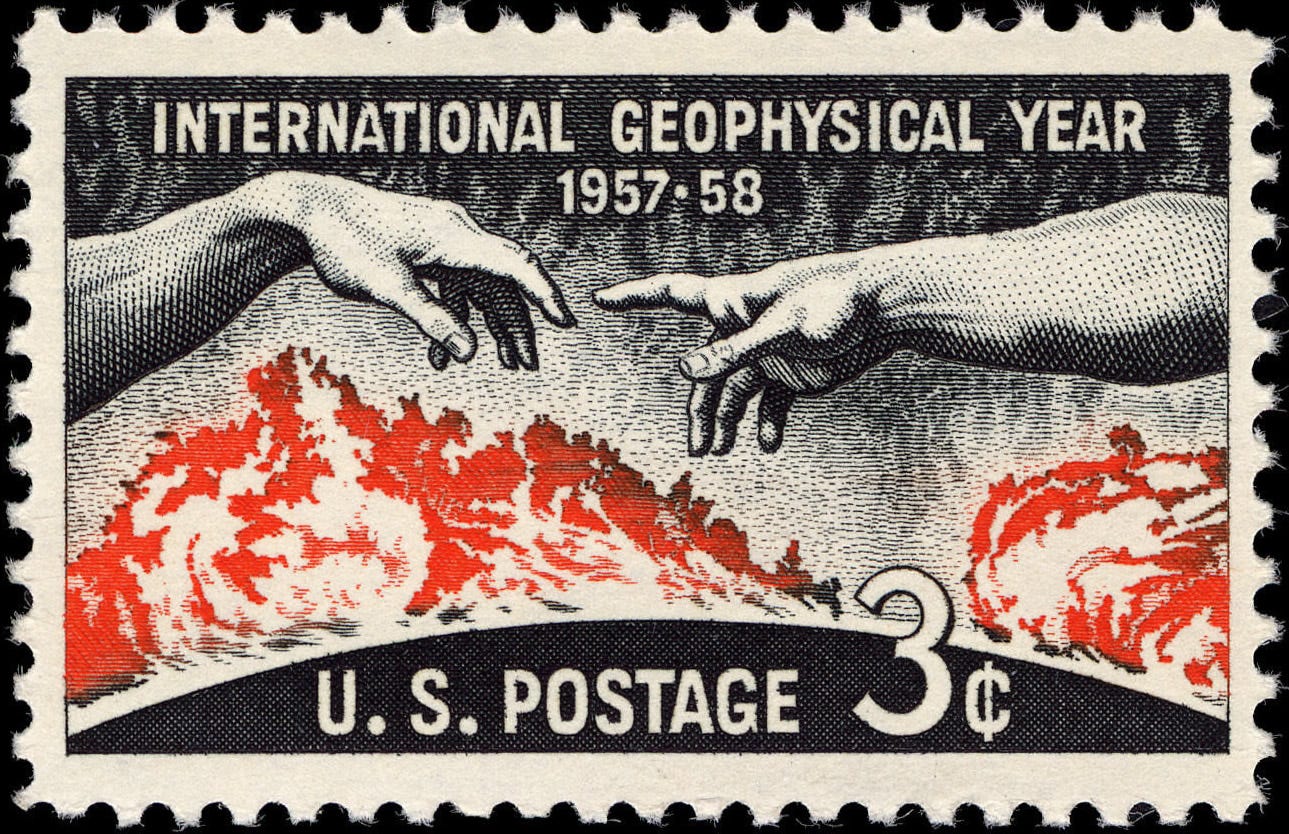

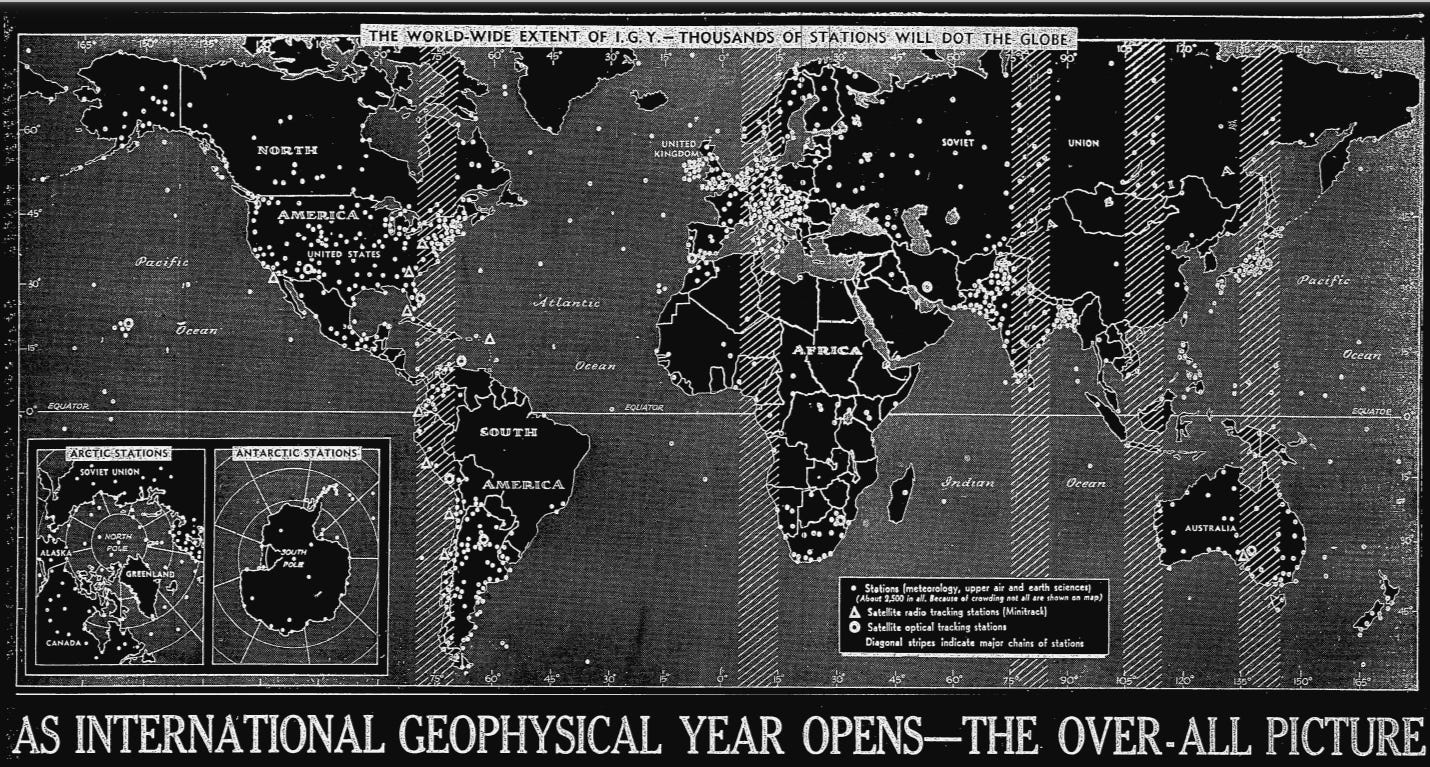

Not surprising, given that Sputnik was the result of the International Geophysical Year (IGY), which was a worldwide program of geophysical research conducted from July 1957 to December 1958. It was a collaborative effort involving 67 countries and more than 4,000 research stations around the world. It was the largest and most important international scientific effort ever undertaken at that time, called “the single most significant peaceful activity of mankind since the Renaissance and the Copernican Revolution'' (Sullivan). During IGY, the US-USSR cooperation included exchange of weather data from satellites, coordinated launching of meteorological satellites, joint efforts to map the geomagnetic field of Earth, and cooperation in experimental relay of communications.

The atmosphere of IGY gave rise to successor enterprises such as the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR), which was established in 1957 as a partnership between the US and USSR. In addition, the inter-academy exchange program existed throughout the lead up to IGY and during the entire “Deep Cold War”, with the notable example of Russia’s chief physicist at IGY, Pyotr Kapitsa, once heading an atomic research laboratory at Cambridge University. This was the environment in which Sputnik was developed, at most the “rivalry” was academic and the “surprise” extremely complex and qualified.

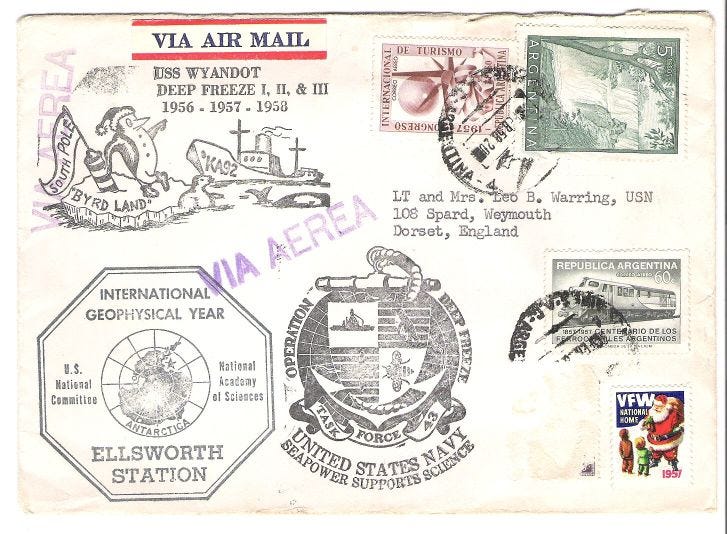

During the IGY, participating countries made a commitment to share scientific data and resources in a planetary effort to establish the mono-cosmography and explore unmapped areas, with a focus on the Antarctic territory. IGY is now called by SCAR “the year that made Antarctica”. Planning for the Antarctic component of IGY had shown the need for a body to coordinate the expeditions in Antarctica and so the Special Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) was formed, another Soviet-US collaboration. There was also an intense focus on the aurora, the sun and the solar wind during IGY, giving rise to the Scientific Committee on Solar Terrestrial Physics (SCOSTEP) and other cooperative organizations. It was essentially the solidification of modern cosmology through cabbalistic committee. The Antarctic Treaty as well as Operation Argus were direct extensions of this re-imaging of the earth and the heavens.

The program generated several tomes filled with technical details of each participating nation’s rocketry and satellite programs. The timeline of Soviet information sharing is less than transparent, but far from panic-inducing. In 1956, Soviet IGY committee chairman Ivan P. Bardin announced plans for a Soviet satellite program during the pre-IGY assembly in Barcelona. The Soviet delegation outlined its plans for a satellite in “great detail”, according to James Van Allen. Although the official announcement was brief, physicist John Simpson would recall a private meeting with ICIC chairman Leonid Sedov, who provided more detailed information about the likely size, orbit, and telemetry frequencies of the future Soviet satellite.

In October of that year, an article in Moscow News outlined the possible dimensions of the satellite, which closely approximated the eventual reality. Nine months later, on the eve of the IGY summit, the Soviet committee provided further information about their project, including brief details about the types of experiments to be conducted on sounding rockets and satellites. In June 1957, Bardin sent a seven-page document with a summary of the project, but no technical information about measuring instruments or telemetry. Later that same month, Soviet Academy of Sciences President Alexander N. Nesmeyanov stated that everything was ready for launching a Soviet satellite, possibly within the next few months. Finally in July, with a full three months left until Sputnik’s launch date, four Soviet rocket scientists visited their British counterparts at the British Interplanetary and Royal Aeronautical Society, providing detailed explanations of the scientific program planned for Soviet satellites.

Technology historian Rip Bulkeley, referencing Radio, a Soviet scientific magazine that published articles that provided significant “intel” on Soviet technology for Western intelligence agencies, summarizes the situation succinctly—

”Nothing better demonstrates the adequacy of this informal Soviet material as forewarning of an imminent launch attempt, than the fact that, three and a half months before it happened, and even before he had seen the copious material provided by Radio in the summer of 1957, RAND analyst Firmin Krieger succeeded in predicting the event to within 17 days. Perhaps a new category of 'open surprise' is needed, for sudden developments in international relations in which the conjuror of future events keeps nothing up her sleeves.”

Captain of the USS Overton

“By May of 1957 we had everything there was to know about the Sputnik. We had the angle of launch, we had the date. It was to be between September 20th and October 4th. September 20th (sic.) was the 100th anniversary of the birth of the father of Soviet rocketry. The 4th of October was the last window that they could launch.”

—Eloise Page, CIA, Scientific Operations Division (SOD) (formerly Technical Guidance Staff)

Eisenhower did not believe the US was in a “space race” with the Soviets. He had no reason to, and his statements are perfectly in line with the reality of the situation—“Never has it been considered as a race; merely an engagement on our part to put up a vehicle of this kind” and “if we were doing it for science and not for security, which we were doing, I don’t know of any reasons why the scientists should have come in and urged that we do this before anybody else could.” (Studies in Intelligence Vol. 61, No. 3) This is the sound of a man responding to a clown-op, sense-making downward into realms of sub-creation.

The CIA’s Current Intelligence Weekly Summary of June 27, 1957, literally quotes public announcements of Soviet officials and IGY scientists. The “surprise of the century” was a media creation, a “political panic”. Karl Weber wrote in his 1972 history of the CIA’s Office of Scientific Intelligence (OSI) that the CIA believed the first satellite launch in history would generate prestige and propaganda power for the country that achieved it. Declassified CIA documents confirm this—

Walter Sullivan, the New York Times chief science journalist, covered the IGY extensively, and his reporting constitutes much of the public record and perceptions of the IGY. If the public was stunned by Sputnik, it would be due to his catastrophic failure. Lucky for Sullivan, his real job was disclosure and dramatization, in which he excelled. To be precise, he was tasked with disclosing Project Argus and dramatizing the events of the Sputnik launch.

Sullivan is a suspicious character, even by NYT standards. Much of his “science reporting” reads like press releases from the Office of Scientific Intelligence, Naval Research Laboratory, or the Atomic Energy Council. Of course, Operation Mockingbird was in full swing at this time and Sullivan appears to be right in the thick of it. First, a Navy officer, commander of the USS Overton (you can’t make this up), then a globe-trotting foreign correspondent who witnessed the closing months of the communist uprising in China, he subsequently headed the Berlin bureau of the New York Times, reporting on the anticommunist uprisings in East Berlin. Sullivan then pivoted to science reporting, basically inventing the category with his assignment to join Operation Highjump, the Navy expedition to Antarctica under Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Schwabstack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.