The American psyche ‘dies suddenly’ in the half-light of a world poised between wars, where old empires are raped and new orders shaped from supple Trauma. As national identity became abstracted, so did national security. The Double War defeated the old world-image and what rose from shattered cities was a mutable specter. Humanist doctrines for haunted polities, they all spoke in stern tones of freedom's fragile defense, yet their true telos is broader, deeper—a preemptive strike against the problem of mass man and his failed gods. An open hand concealing a fist, binding allies in a network of protocols. A fist concealing claws, spidering down the telluric Spine, ripping through the logic of life.

The Cold War logically follows lend-lease, as MK-Ultra followed from ‘universal human rights’, same as chip-pig cyber-economies shall follow ‘freedom from want’, and finally, ‘freedom from fear’ will deliver the world into eternal post-cognitive goontopia. Further and further into abstraction we fall, until we clip through the geography of low virtual realms. Security becomes a totem ringed by thunders of the upper deep, a floating island upon the maelstrom of an interconnected world, ethereal and vast, where ideological boogey men evolve into hypnagogic hat men, lurking at the eye’s gates.

There can be no borders in this cosmography. Not even the social ordering axis of Sex can be protected. There is no defense of the physical here, no simple wall against invasion, but a new vision— a liberation from the dimension of human experience, a New Deal for the world-image.

The Cold War era, particularly from 1947 to 1950, marked an inflection point in defining “national security.” The Truman administration, through the Truman Doctrine in March 1947, the Marshall Plan announced by Secretary of State George Marshall in June 1947, and the establishment of the CIA and National Security Council via the National Security Act in July 1947, solidified the framework of American national security policy. These developments were driven by an extension of liberal ideologies, not traditional conservatism, embedding national security within the fabric of American liberalism as an extension of the New Deal principles applied to foreign policy.

The concept of national security, as a distinct American doctrine, first began to crystallize during the late 1930s. President Franklin D. Roosevelt deployed the term during 1937-1941, significantly more than all of his predecessors combined, especially in the context of globe-spanning threats and military technologies. This period saw a shift in American perception of self-defense, from strictly territorial to a broader, ideological scope, in response to an ever more interconnected and interdependent world.

This novel definition of national security was an extension of American liberal “welfare state” powers, called a “New Deal for the world,” which sought to protect against global ideological threats, much like domestic policies aimed to shield citizens from economic adversities. This marked and ideological transformation within U.S. political thought and policy technology from “hemispheric” isolationism to a proactive, paranoid international stance, influenced heavily by the psycho-engineering campaigns of the mid-20th century, setting the stage for America's long-term global engagement strategy.

In the two decades before the U.S. entered World War I, Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan’s The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660-1783, had “as profound an effect on the world as had Darwin’s Origin of Species.” This period witnessed fantastical war scares with Chile, Brazil, and China, coinciding with the emergence of popular science fiction that depicted Yellow Peril, of Demon Scientists and Anarchists, armed with fearsome weapons, influencing public and political perceptions of security threats. These cultural and geopolitical anxieties fueled the preparedness movement of 1915–1916, predominantly supported by East Coast law firms, banks, and elite universities, which advocated for a substantial U.S. military buildup.

Jack London's 1910 science fiction story, "The Unparalleled Invasion," envisioned a future where Western nations, alarmed by China's expanding population and influence, resorted to biological warfare, deploying "strange, harmless-looking missiles, tubes of fragile glass that shattered into thousands of fragments on the streets and housetops," to decimate the Chinese populace. There is evidence that London, an atheist socialist, was not motivated by “racism,” for him it was a matter of simple math: "There was no combating China's amazing birth-rate. If her population was 1000 millions and was increasing 20 millions a year, in twenty-five years it would be 1500 millions-equal to the total population of the world in 1904.”

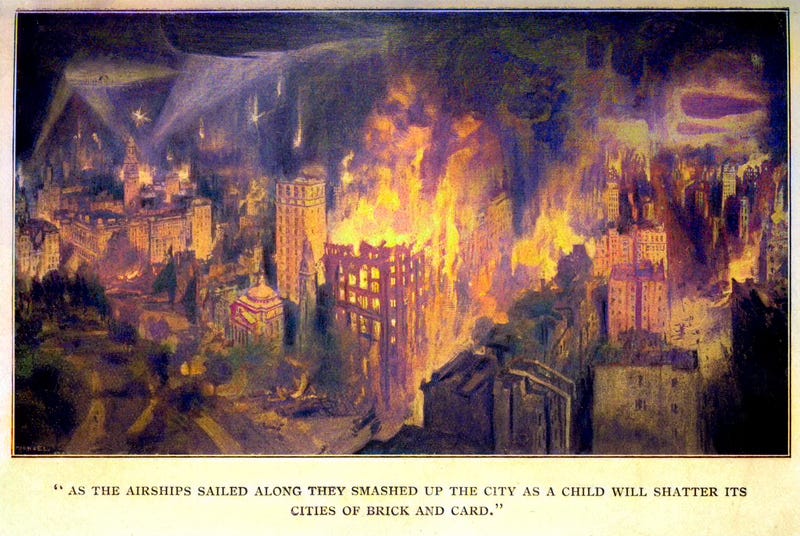

No one injected the idea of global destruction and hegemony through technology at the level of HG Wells, an active member of the Fabian Society in the early 1900s, where he pushed for more radical reforms and criticized the group's cautious, gradualist approach to socialism. His proposals for restructuring society and advocating direct action led to conflicts with the leadership, particularly with George Bernard Shaw and Sidney Webb, resulting in his departure from the group in 1908.

The Fabian Society, founded in 1883, was a gathering of subversive intelligentsia and gay warlocks which, after a fashion, realized Weishaupt's Masonic illuminism or Mendelssohn's Jewish illuminism (Haskalah). At the time, John Stuart Mill's political economy in England and Comte's positivism in France disturbed the psyches of many prominent intellectuals, fueling “free thought.” E. R. Pease, the society's historian, notes the direct influence of Thomas Davidson, founder of the pseudo-mystical, New Age precursor Fellowship of the New Life, which evolved into New York's Ethical Society of Culture.

The Fabian Society was further shaped by assimilating the utopian socialist ideas of Robert Dale Owen, an ardent “scientific” Spiritualist, feminist and architect of the Smithsonian Institute. Notably, early members included freemasons and several other spiritualists, some later aligning with Madame Blavatsky's theosophy; Founder Frank Podmore's involvement in Masonry, occultism, and socialism is particularly notable. Among early intellectuals joining were Bernard Shaw in 1884, Sidney Webb, Lord Passfield, and Sydney Olivier. Mrs. Annie Besant also joined, then head of the theosophical movement. The society explored Babouvism, Marxism, Bakounist anarchism, and other social democratic groups but, composed mainly of intellectuals, bureaucrats, and journalists, preferred drawing-room meetings over street riots. A key strategy was "permeating" other societies with Fabian ideas, a tactic termed "Fabian." The Fabians are emblematic of the “slow march through the institutions.” But this strategy was indeed too slow for the likes of Wells.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Schwabstack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.